Interview with Jeff GIBSON

the ephemera interviews

In this series of interviews artists directly involved in ARIs and artist-run culture 1980- 2000 speak about the social context for their art making and provide insights into the ephemera they produced or collaborated on during this period. Artist ephemera includes artworks, photocopies, photographs, videos, films, audio, mail art, posters, exhibition invites, flyers, buttons and badges, exhibition catalogues, didactics, room sheets, artist publications, analogue to digital resources and artist files.

BIO

JEFF GIBSON LIVES AND WORKS IN NEW YORK, USA.

Brisbane-born and raised, Gibson studied journalism, media theory, modern history, and the visual arts at the Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education (now the University of Southern Queensland) before moving to Sydney in 1981 to co-manage an artist-run space, Art/Empire/Industry.

He then studied art and critical theory at Sydney College of the Arts (1984–85) and co-managed another artist-run gallery, Union Street (1985–86). Over the following twelve years he mounted numerous solo shows at commercial and public spaces in Sydney, Brisbane, and Melbourne, including the Mori and Gitte Weise galleries in Sydney, the Michael Milburn Gallery and the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane, and Tolarno gallery and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne.

During that time he participated in group shows in Australia and abroad, including exhibitions at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and Artists Space in New York. In 1988 he began working for Art & Text magazine, becoming associate editor in 1991 and senior editor in 1994.

He taught in both the painting and print media departments at Sydney College of the Arts from 1991 until 1998, at which point he moved to New York to work for Artforum magazine where he is currently managing editor. Since arriving in New York, he has produced two artist’s books, exhibited on the Panasonic Astrovision screen in Times Square as part of Creative Time’s “59th Minute” program, and mounted solo shows at the New York Academy of Sciences, Stephan Stoyanov Gallery (New York), and The Suburban (Chicago).

Throughout January 2011, two of the artist’s videos were projected onto the facade of the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York, as part of a curated series presented by Light Work and the Urban Video Project. His video Metapoetaestheticism, 2013, was exhibited in the 2014 Whitney Biennial.

INTERVIEW – January 24, 2015

1980’s Social History: Jeff tell me about the milieu you experienced during the early to mid-1980s as a young artist living, working, collaborating in Toowoomba and Brisbane, what sort of world was this Queensland for you?

JG:

I attended what was then the Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education (DDIAE) in Toowoomba from 1976 through 1980. I was born and raised in Brisbane but elected to study in Toowoomba because I was restless and wanted a change of scenery. I was a rebellious, dyspeptic upstart primed for punk. Drawn to art, music and exposition I started out in journalism and media studies since writing seemed a more sensible option than art.

I glommed onto Marshall McLuhan and the Sex Pistols, then switched, after a year of journalism, to the art department. I dove headlong into art and soon after also formed a band—the Sad Cases—with Stephen Butler, Kieran Knox, and James Rogers.

I found Brisbane very oppressive at that time. I would participate in demonstrations and street marches and then retreat to Toowoomba. I guess to some extent I “dropped out.” I lived in farmhouses—dystopian art punks in a rural/hippie setting. It was fun in its own way, but of course Toowoomba was even more reactionary than Brisbane.

As an anti-authoritarian malcontent, I had plenty to push against. I learnt an awful lot at college but by the time I was half way through my visual arts degree it seemed to me that the culture and politics of the state of Queensland were not conducive to a full creative life, so I committed to moving to Sydney as soon as I’d completed my course.

PA:

Tell me about your exodus from Queensland in 1981?

JG:

I didn’t really participate in the artist-run Brisbane scene. I bummed around for a year after high school then moved to Toowoomba in 1976 to study for four years. After that, I took a bee-line for Sydney. As soon as I got to Sydney, I helped open a gallery on Sussex Street—Art/Empire/Industry—with James Rogers, Gayle Pollard, Calvin Brown, and Glen Puster. There were other artist-run spaces in existence, but it was all pretty rogue and subrosa until the mid-‘80s when ARIs became more formally integrated into the art world, attracting a little assistance from the Australia Council. A/E/I only lasted a year (it resurfaced later without me and James). The absurdly cheap-to-rent loft was sold out from under us. Shortly after, I started a postgrad course at SCA and co-organized another gallery, Union Street, with artists Deborah Dawes, Deborah Singleton, and Jelle van den Berg.

Things were changing. There was a new professionalism creeping into artist-run culture in Sydney. An actual scene was beginning to take shape. Art & Text delivered a fresh discourse that launched a seemingly cohesive generation of postmodernists quite distinct from previous generations of artists, even progressive ones. Stephen Mori, Roslyn Oxley, and Kerry Crowley opened galleries that were sympathetic to these concerns. ARIs in career-minded Sydney were at this point as much professional launching pads as they were cradles of experimentation. Comparisons were often made between Union Street and the East Village New York artist-run galleries that catapaulted 80s art stars like Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, and Robert Longo into the stratosphere. Obviously, the cultural and financial stakes and rewards were much lower in Australia.

In time I came to know more of early Brisbane, Sydney, and Melbourne artist-run spaces through conversation, conferences, travel and the occasional reference in Art & Text, Art Network, and Tension magazines.

PA:

A brief biography Jeff?

JG:

As a kid, art barely figured in my family life or my schooling. It wasn’t offered as a subject at my high school (a Christian Brothers college in South Brisbane). Yet my brother, Ross, and I were, for whatever reason, naturally drawn to creative pursuits—he mostly to literature, me to art; we shared/share a love of popular music.

Making art in one form or another was simply what I most wanted to do with my life. Once I enrolled in visual arts at DDIAE I felt I’d found my path, and I never looked back. There were certain lecturers whom I liked or admired and whose feedback and assistance I appreciated, but it was really the milieu, the relationships forged among fellow students that most enabled my development. I was highly motivated and threw myself into my work.

PA:

Tell me about the Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education?

JG:

DDIAE was great. I was so psyched to be learning about and making art that I just ate it up—decent studios delivered a broad sweep of media—and made a ton of stuff. I later did some time at Sydney College of the Arts (SCA) in the print media and painting departments, both of which I ended up teaching in for a few years. And I also have a trove of unrepeatable good and evil advice courtesy of Paul Foss, whom I worked alongside at art/text for ten years.

PA:

Pop Culture- Tell me about the popular culture and music that mattered to you most at this time?

JG:

The Saints and the Sex Pistols blew my mind. We had to make our own entertainment in Toowoomba, so a few of us in the art school formed a band, playing 100-mile-an-hour, anti-everything dirges at parties, bars, halls, and so on. Most fun ever. There was an off-campus, student-run café and gallery, the Dancing Bear, run by Sandy Brown where everyone hung out. The band would play in the National Hotel on Friday nights on the same block, which was in the skid row end of town. Perfect setting. I visited Brisbane every so often but usually only briefly and for particular shows at the Institute of Modern Art or the Queensland Art Gallery. Weirdly, I recall seeing Clement Greenberg speak at the QAG when it was still housed in a government office building, Mount Isa Mines from memory. I didn’t watch much TV during that time. I was busy making art and playing loud, fast music.

PA:

This year marks the 40th year anniversary of the IMA, tell me a little more about the role the IMA played in your own personal experience during your early years as an art student living in Toowoomba?

JG:

The IMA opened my eyes to contemporary art. I started going there in 1976, in my first year out of school. It felt like a portal to another world, a world I desperately wanted to live in. I went there whenever visiting Brisbane from Toowoomba. It was an oasis in an art-cultural desert. I remember its first director, John Buckley, being dragged over the coals in the mainstream media for wasting tax-payers’ money on a Carl Andre exhibition consisting of steel plates arranged geometrically on the floor. But, again, I was living in Toowoomba, then split for Sydney, so can’t speak with authority to the relationship between the IMA and other arts organizations, big or small.

PA:

Tell me about any measure of support, patronage and interest from established Brisbane/Qld galleries you received during this time?

JG:

I didn’t seek out support or patronage from Brisbane galleries in the early 80s because I was preoccupied with A/E/I and then postgrad studies at SCA. Once Union Street was up and running I became more interested in reconnecting with Queensland artists and organizations. I signed on with Mori Gallery in Sydney after Union Street folded and began taking a more active interest in the IMA and the Brisbane galleries. I had a vague association with Michael Milburn and showed there once in 1991. By 1988 I was working for Art & Text, which connected me in one way or another to a broader national network of ARIs, CASs, museums, and commercial spaces. At that point I also started writing criticism.

PA:

Exodus: So many artists fled Queensland during The Police State eighties?

JG:

The threat of police harassment was ever present in the late ‘70s. I’d been carded several times in my senior year of high school and first year out for just hanging out and looking different. It was a hostile environment for art. I wanted to grow and learn and be part of something meaningful, none of which seemed possible or worth the aggravation in Queensland. I couldn’t wait to get out and get on with the job.

PA:

NSW ARIs: Art/ Empire/ Industry – the models, methodologies, motivations for this ARI?

JG:

Yes, Queensland artists Gayle Pollard, Calvin Brown, and Glen Puster were a year ahead of me at DDIAE. They had all moved to Sydney straight out of college and found an incredible space in Sussex Street on the fringe of the CBD that was being sublet at a ridiculously low price. They invited artist James Rogers and myself to join a collective and run a gallery there. From memory I arrived early January 1981 and the gallery opened a month later. It was 2000-square feet of raw, open factory space (with three floors of lofts above, in which we lived and worked). It was a bohemian paradise, vermin and all. It was also part of a last gasp for the inner city SoHo-style defunct industrial-district, artist occupations. In any case, it only lasted a year but in that time we staged about a dozen shows along with a smattering of events. We showed our own work and the best of whatever else was on offer, determined by a more or less democratic process.

It was a great introduction to the Sydney art world, which was accommodating in some quarters, and not so much in others. With hindsight, that year marked the end of one chapter of Australian contemporary art and the beginning of another. It was the end of ‘70s post-object art (think: conceptualism, experimental music/dance/theatre) and the beginning of ‘80s postmodernism. When Art & Text appeared in 1981 (the year of A/E/I’s existence) I felt the ground shift immediately. Four years later, Union Street inhabited a very different landscape.

The program at A/E/I was patchy and schizophrenic but there were definitely some cool shows and happenings. Artist John Gilles lived there some, if not all, of the time, contributing an interesting program of experimental music and performance. Once we were kicked out of the building, James, John, and I peeled off and Calvin, Gayle, and Glen opened a second iteration in Kings Cross, which I showed at but have little recall of the program.

PA:

And the space between Art/ Empire/ Industry and the Union Street Gallery?

JG:

An awful lot happened between 1981 (A/E/I) and 1985–1986 (Union Street). The Sydney real estate market had blown up and inner-city living had become a thing. Artists were flushed out of the CBD to the edge of the inner city—Ultimo, Pyrmont, Newtown, Chippendale, Surry Hills. Meanwhile, as I mentioned, the intellectual tenor of the art world had changed and a new batch of galleries had opened that championed the post-Pop and neo-Conceptual art that went along with it. In 1984 I enrolled in postgraduate studies at SCA, a pro-theory art school that embraced these changes wholeheartedly, in certain departments at least.

Union Street sprang from the postgrad department at SCA. Debra Dawes, Deborah Singleton, and myself were all enrolled there together in the painting department. The fourth member of the Union Street collective, Jelle van den Berg, was a painter and married to Debra Dawes.

We set up on the ground floor of one of a row of four two-story terrace houses perched at the edge of the Darling Harbor development, which was just commencing. I lived on the ground floor of the adjacent house in what was previously a Chinese restaurant. Whereas A/E/I offered 2000 sq ft for $20/week, Union Street operated out of a space about a quarter as big and fives times the rental. We showed our own work and, once again, the best of whatever else was on offer, a good deal of it being drawn, not surprisingly, from a pool of ever-ready SCA students and lecturers. It was compact and efficiently run.

The shows were frequently reviewed in the Herald (thanks mostly to Terrence Maloon) as well as in the art-critical press. Most exhibitors, including all the founders, went on to secure gallery representation. We didn’t claim to be evading or countering hegemonic forces, just doing it for ourselves in hopes of making a mark.

We eschewed the heroic rhetoric of “alternative spaces” and focused our energies on simply presenting as interesting and with-it a program as we could manage. It, like most ARIs, was a clubhouse, providing solidarity and opportunity to its members.

PA:

Other NSW ARIs you recall now?

JG:

The ‘80s are a blur to me. So much happened and it was so long ago. I really don’t recall. And now it’s buried under 160-plus issues of Artforum.

PA:

First Draft, how was this ARI different to Union Street?

JG:

Union Street had a Sydney College vibe. First Draft had a CoFA vibe. SCA was hypercritical, CoFA was more forgiving. I was down with both camps. They did some good shows. That was the first iteration at least. I’m not well enough informed of the history to comment on anything beyond that.

PA:

Did this confluence of ARI infrastructural work personally transform you in some way(s)?

JG:

Sorry, no epiphanies. But I continue to value working alongside other artists. With art being such an industry now, there’s something very affirming and clarifying about hanging out with artists, talking about art and its relations.

PA:

This vibrant proliferation of Australian artist-run culture during the 1980s, why do you think/ feel it burgeoned Jeff?

JG:

It burgeoned because it provided opportunity, principally. There was a distinct growth or expansion of interest in contemporary art in Australia in the 80s and artist-run spaces and the like grew along with it. I think such activities are generally born of a desire for artistic exchange and for exposure of one’s wares and whatever opportunities that might bring.

PA:

Tell me about your occasional 1980’s return trips to Queensland Jeff?

JG:

My returns were sporadic. I’d do the rounds when I was in town, but, again, I’m foggy on the details. I have many sacred memories of Toowoomba but have only returned once, and that was just for the hell of it, so I can’t comment on that. Brisbane has obviously changed profoundly. As the Bjelke Petersen regime crumbled, I watched a vital, driven scene arise. It all seemed good to me.

PA:

Thank you for your time, your considered and vivid recollecting and for your thoughtfulness Jeff I am truly grateful for this interview.

JG:

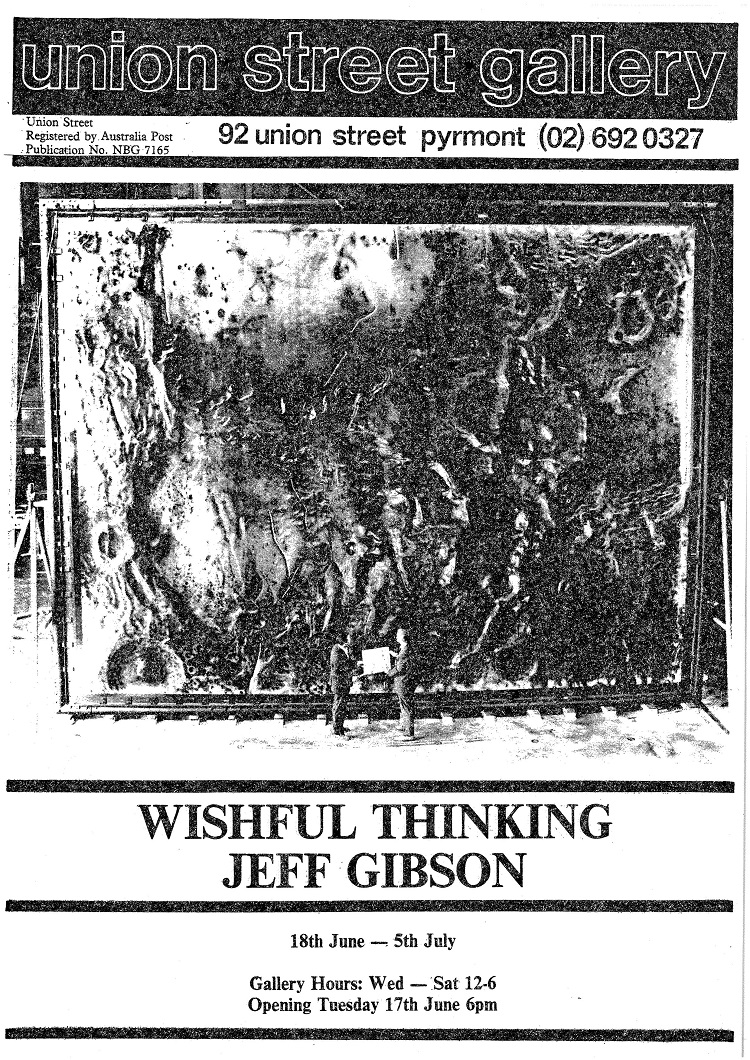

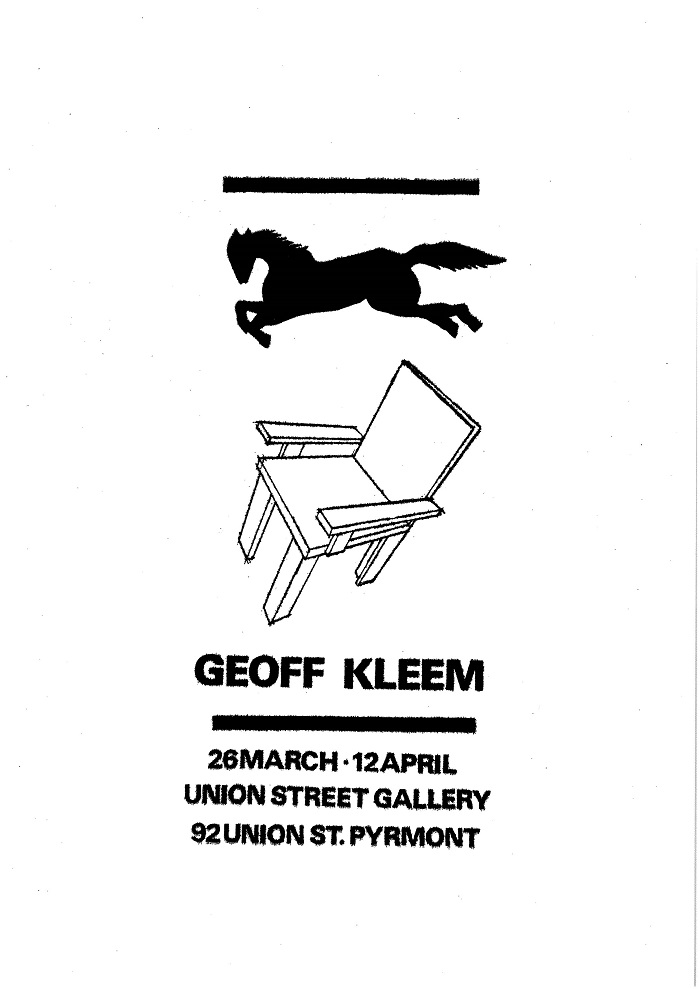

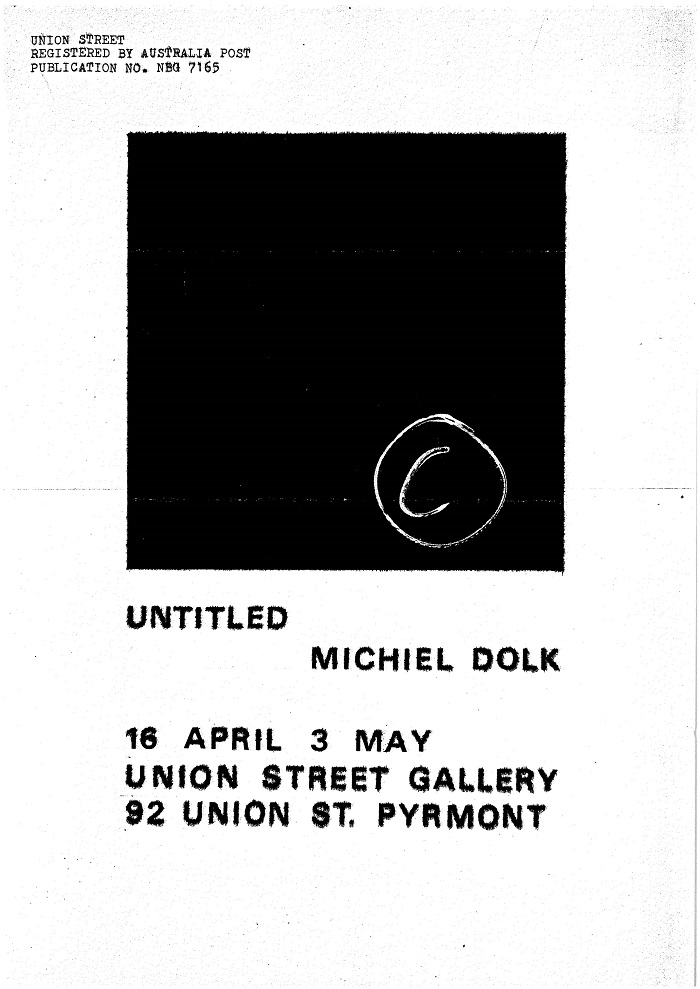

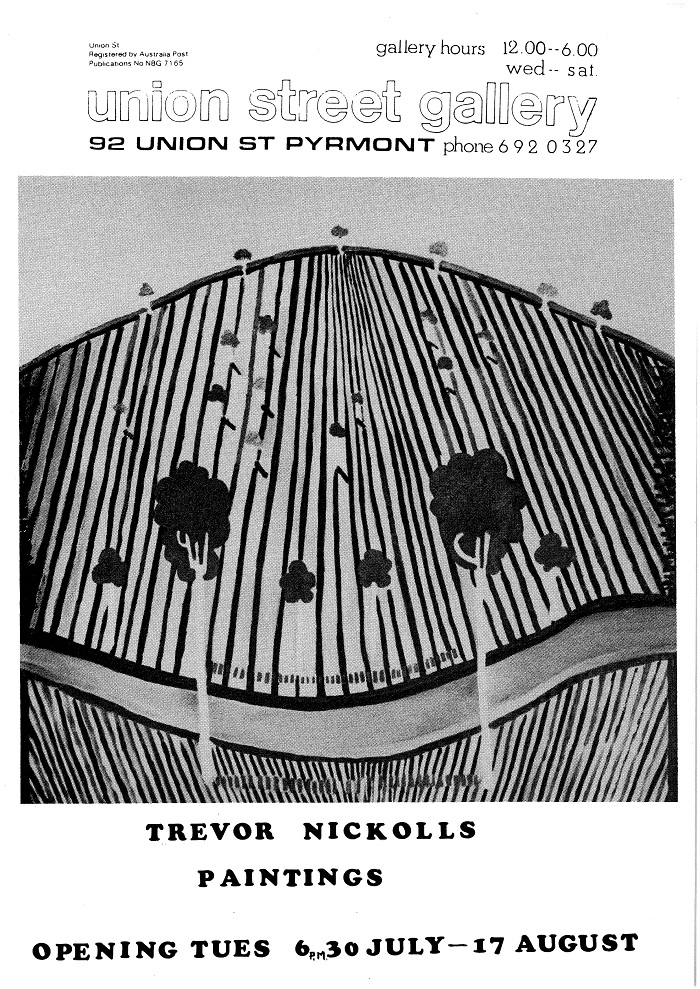

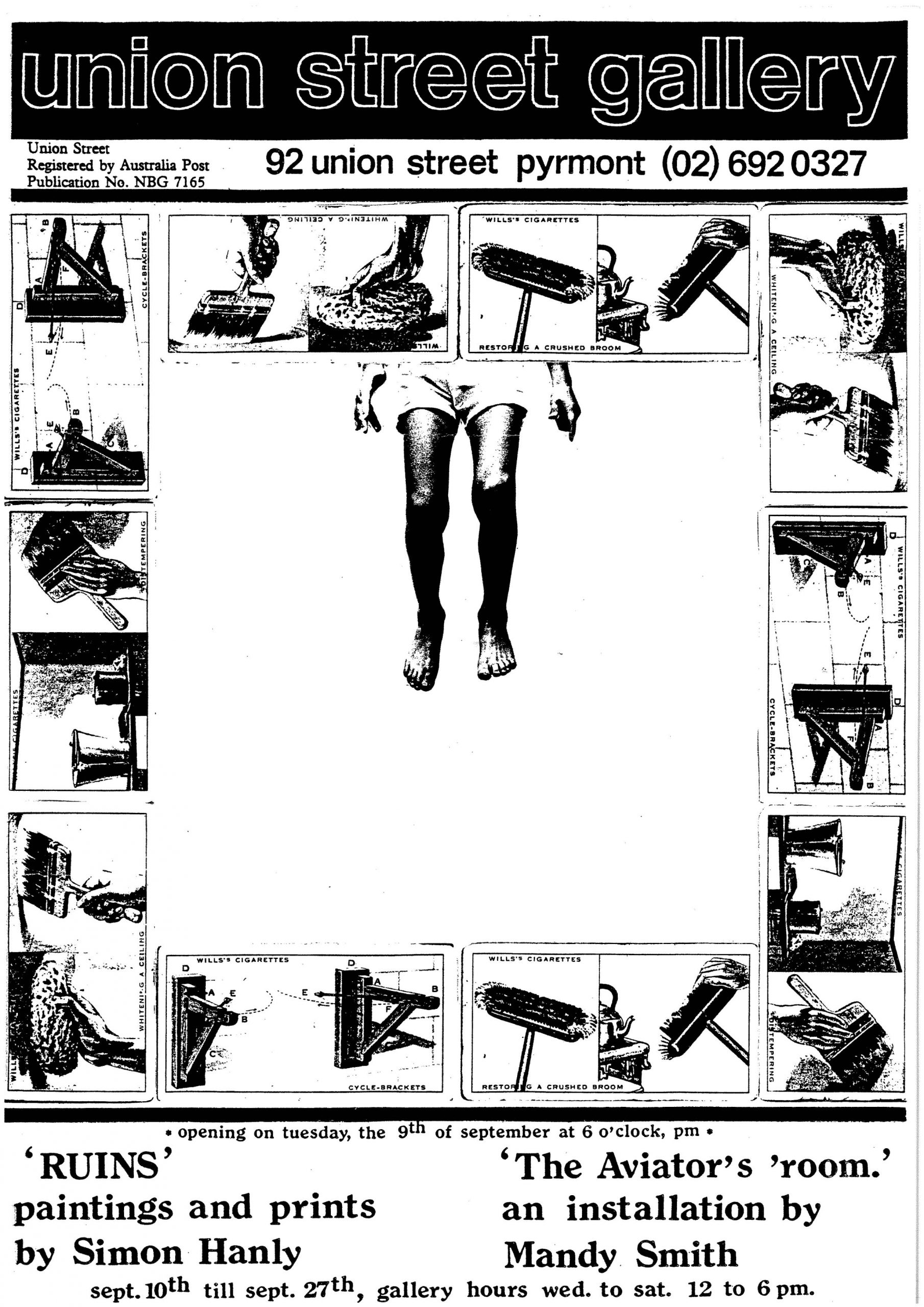

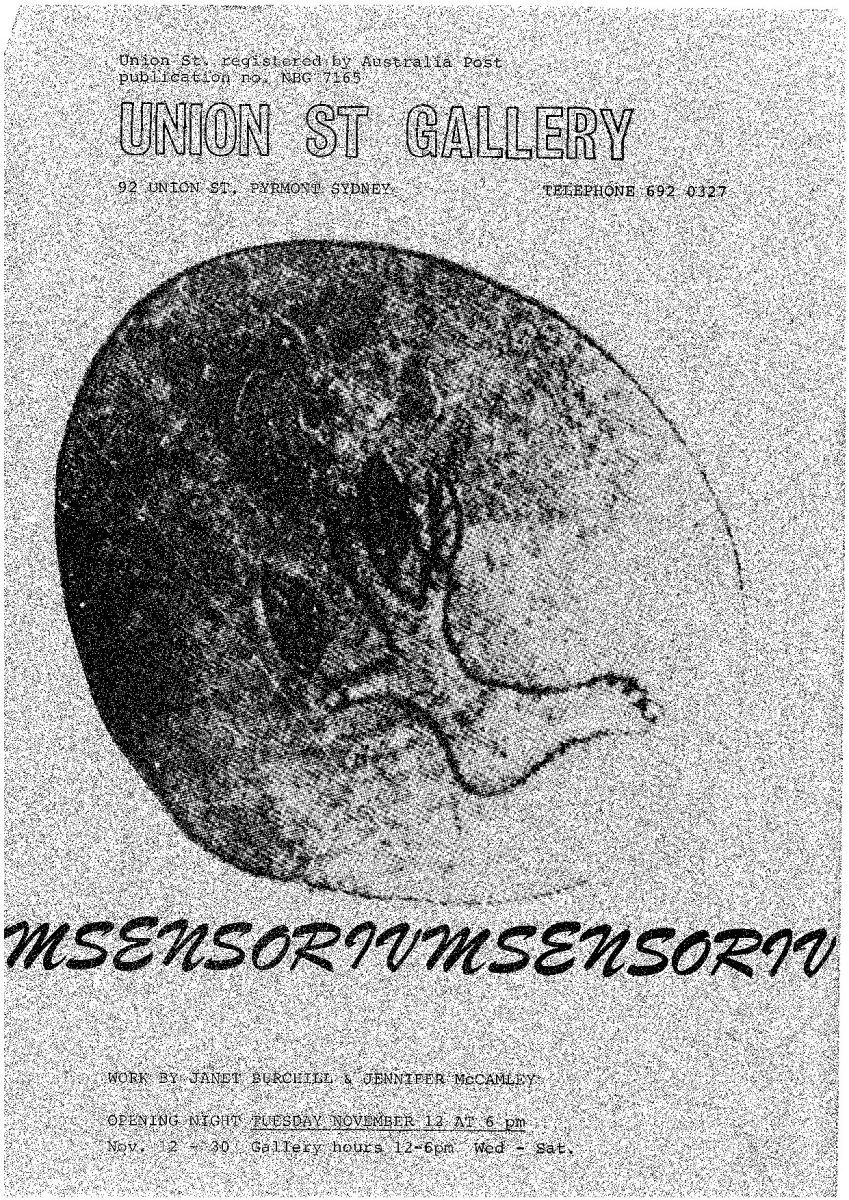

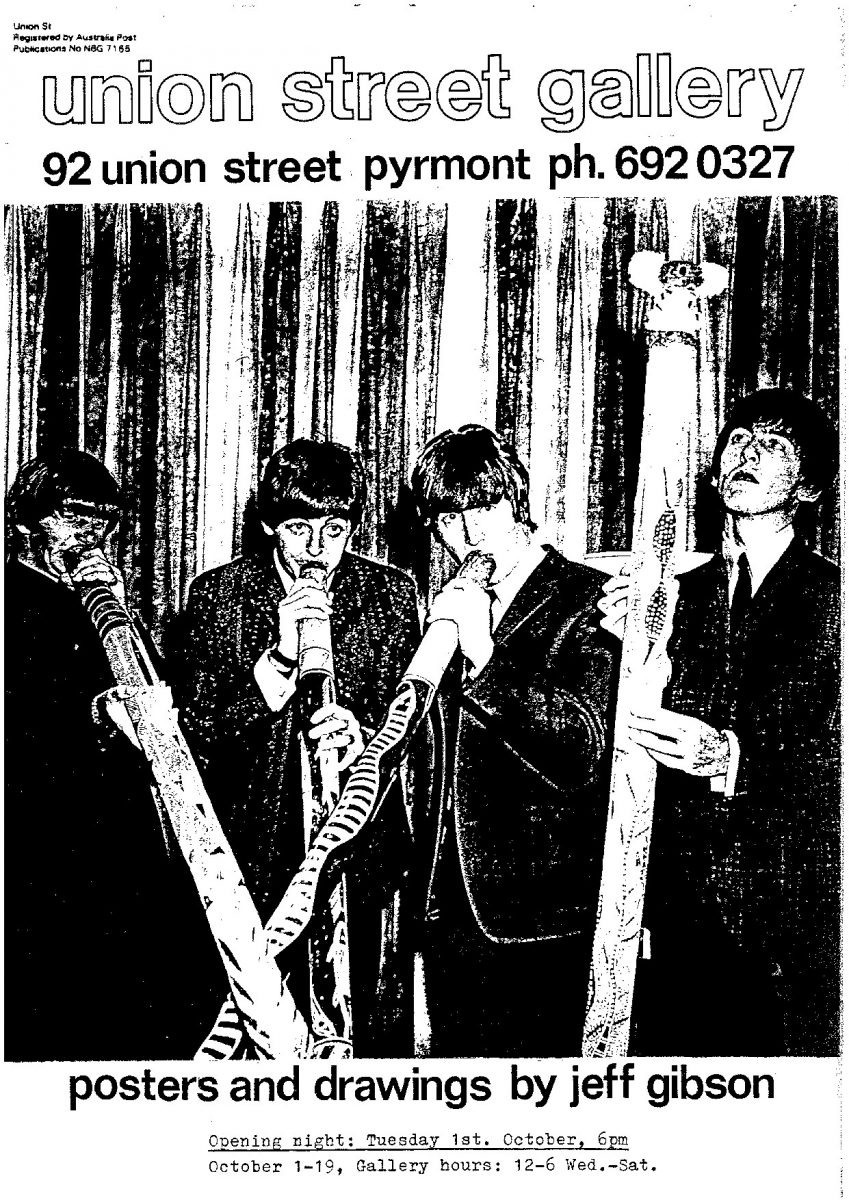

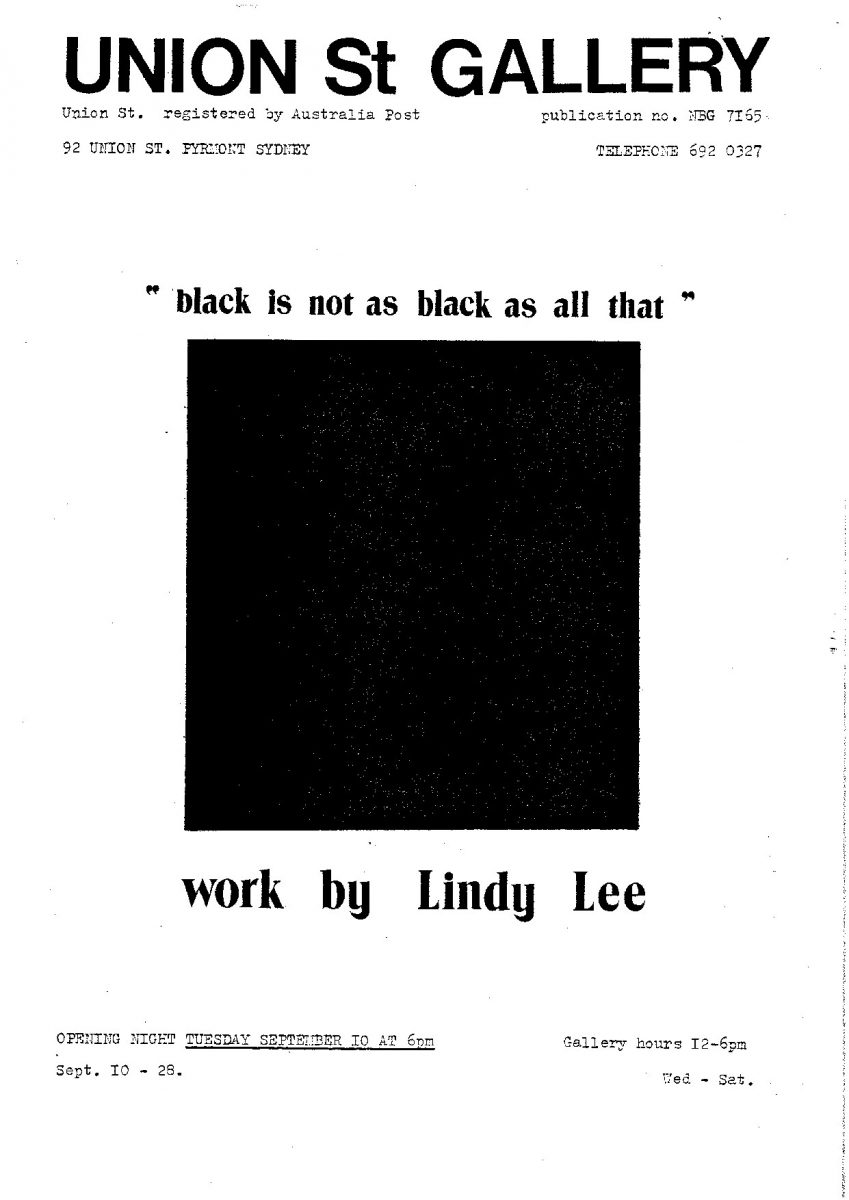

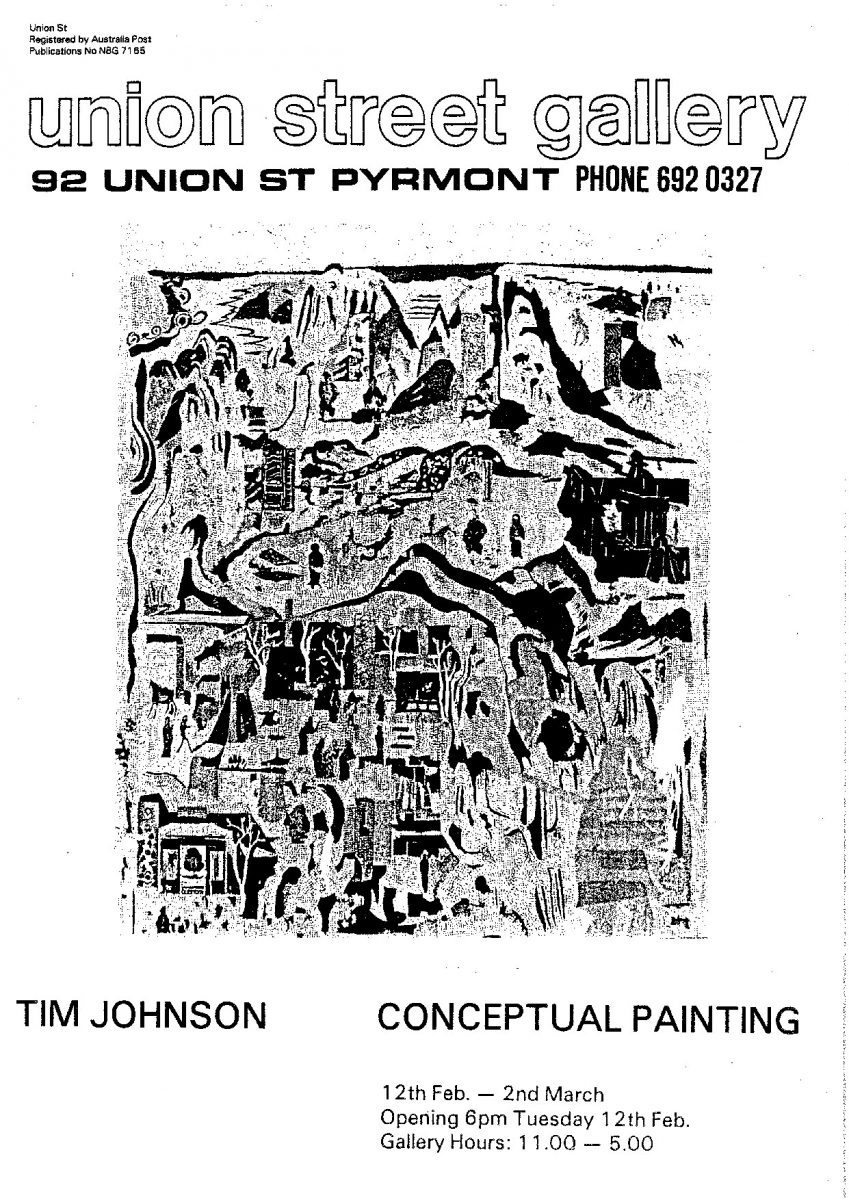

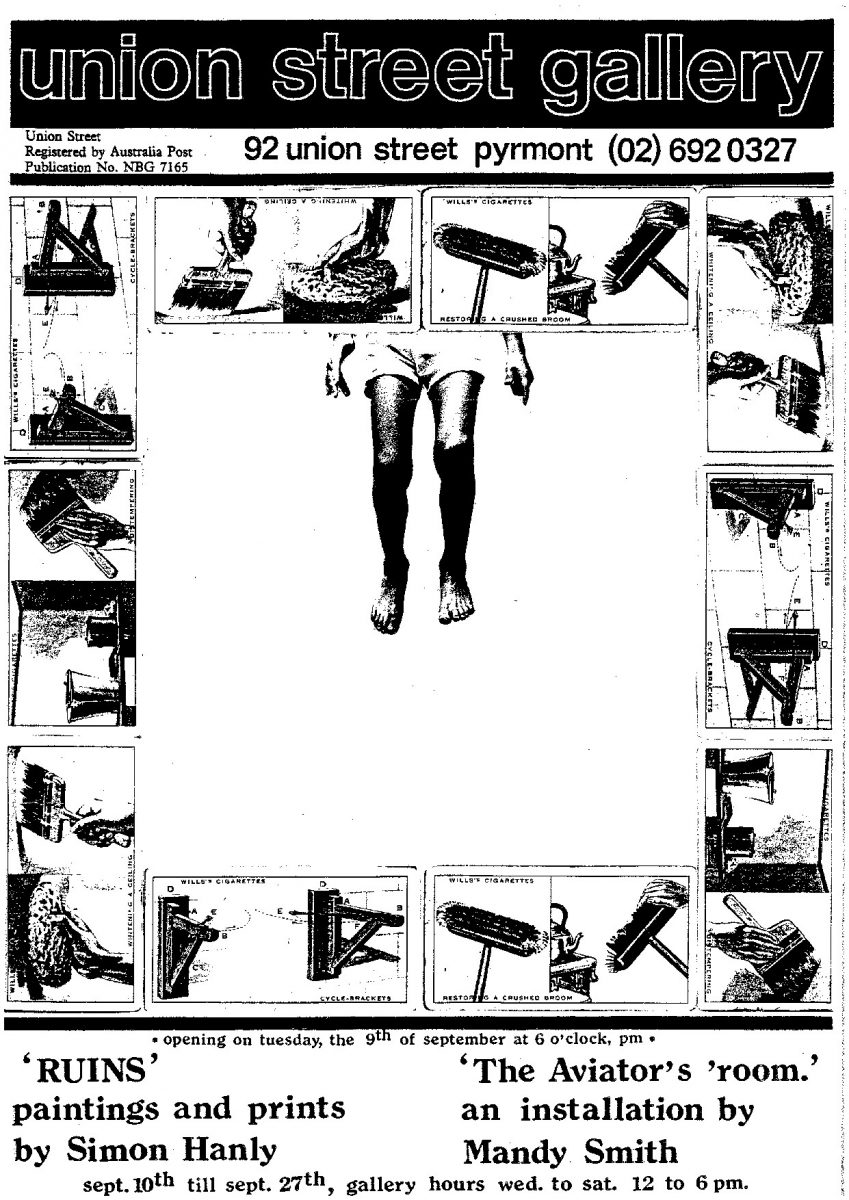

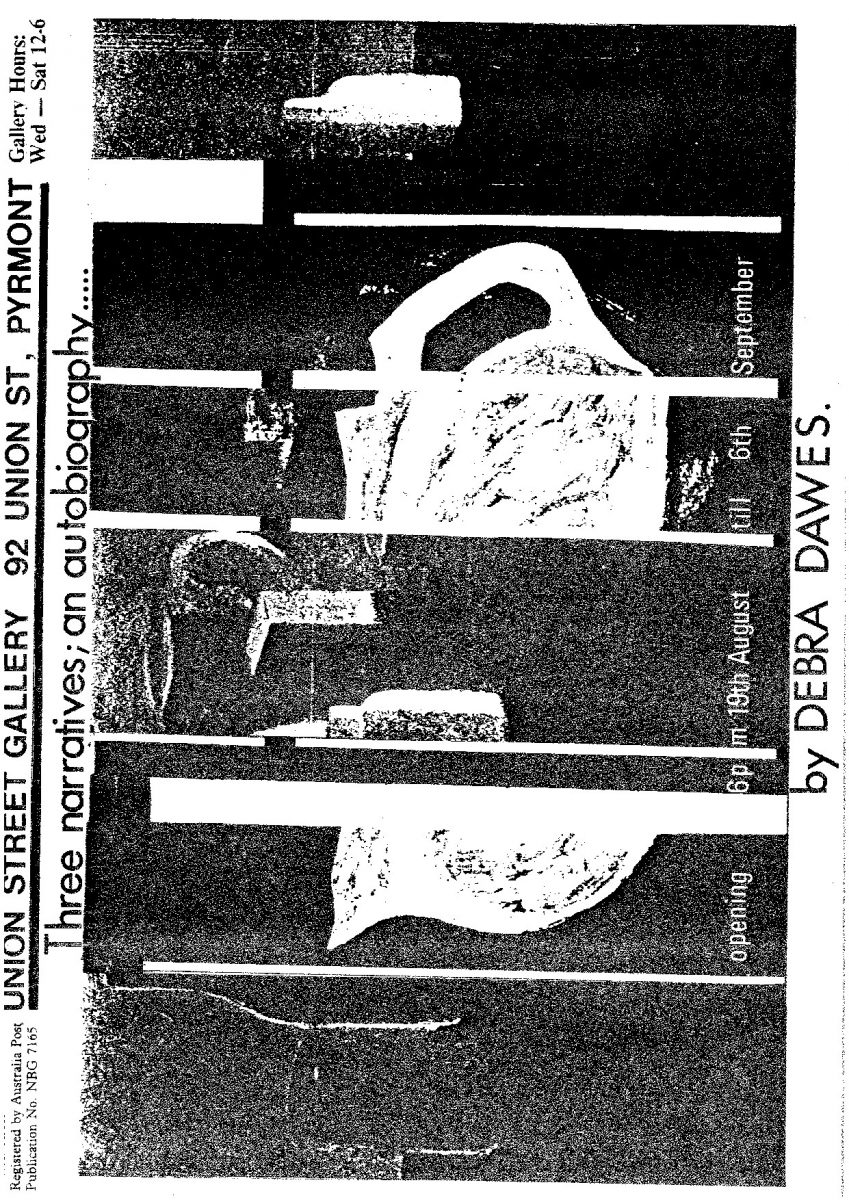

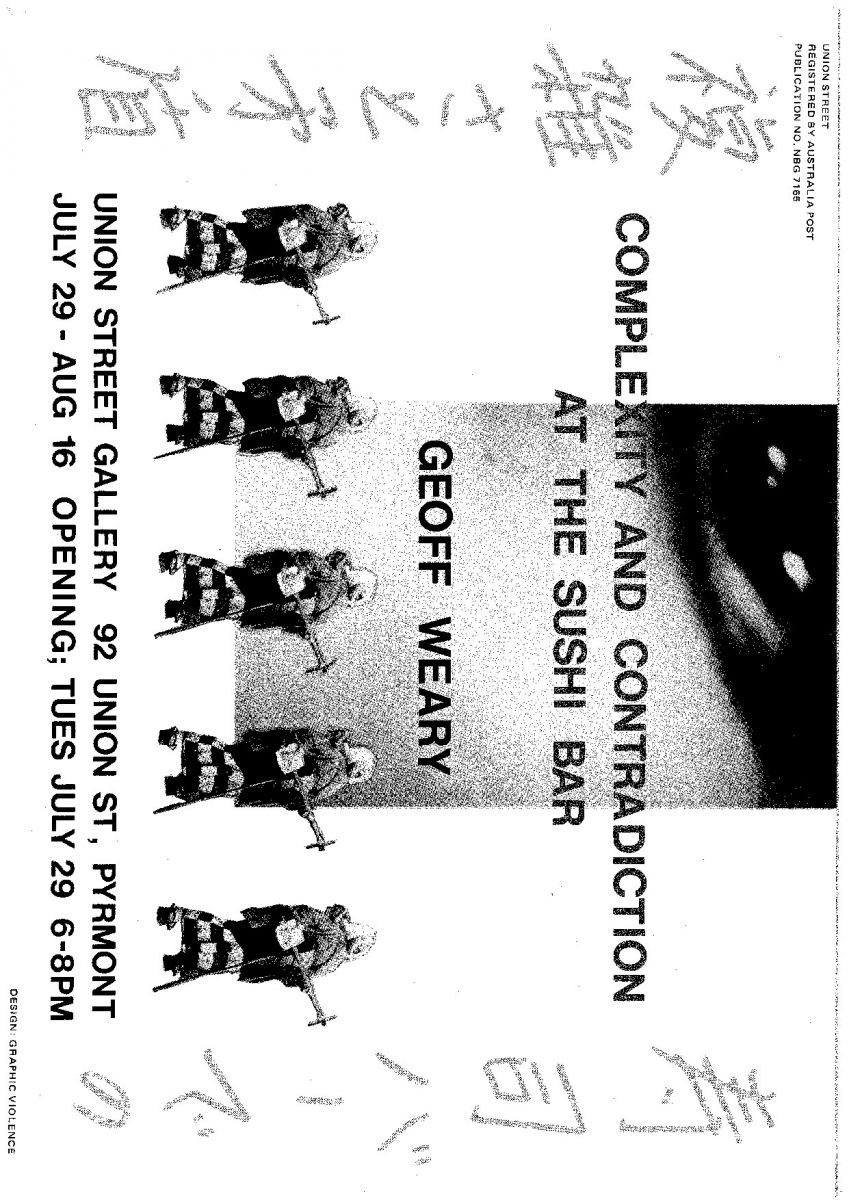

The invite shared here are examples of the photocopy exhibition invites we sent by mail to members on our mailing list each month.

Artist Website

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art, Empire, Industry – Artist-run, Sydney

http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/?exhibition_id=1236