A Sign of the Times – Ian McIntosh

Looking back is a challenge. You might say that life is a work in progress, but so too are one’s memories. What we hold onto, and what we let go, seem to be always in flux. A meeting with old friends or family can bring certain memories to the fore that were best left alone. For instance, I don’t recall being chased by a mad person with an axe in Darwin in the late 1980s. Should I? The horror. But my sister insists on the truth of it, and even though she said a large wooden cross and an old bible were centre stage, I have no recollection.

However, I do remember a similar instance but only because it was funny – in retrospect – and worthy of retelling. (If there was no opportunity or desire for storytelling, or for lessons to be shared, then why hang on to it? Let it go.) This incident was at an Aboriginal Land Council meeting in the Northern Territory and one embattled claimant who was living at odds with his kin put a shotgun to my head and said he going to let me have it with both barrels. His brother, horrified at the prospect, stepped in saying, ‘No, no, no, you can’t do that.’ ‘Why?’ this man yelled. ‘Just use one barrel,’ his brother said, ‘I want to go goose shooting later.’

My experiences in Aboriginal Australia shaped my passion for art and activism, in particular, an earlier stint in Queensland’s north-west in the early 1980s. A mind-spinning, life-altering experience as a welfare officer in Mount Isa, Doomadgee, Camooweal, and Urandandjie and all those fantastic sounding place names, was to be the spark for my involvement in 1984 in the Brisbane art scene with ‘One Flat’ and the wonderful artists Jeanelle Hurst, Hollie, Russell Lake, Adam Boyd, Adam Wolter, and Eugene Carchesio.

The extreme violence and indifference I had witnessed within the Aboriginal community, and towards the Aboriginal community by society at large, and the fact that even the highest ranking Queensland politicians would openly say that it was in no-one’s interests to represent the hundreds of the downtrodden living in the open air camps along Mount Isa’s riverbanks, embittered me to the core. These people who had drifted in from the missions, from foreign-owned cattle stations, or been forced off their traditional lands by mining, were considered sub-human and not worthy of respect or rights.

I was outraged back then and I still am. This was the great Australian silence observed firsthand, at its most stifling.

I was no stranger to the silence. I’d had my own personal experience much earlier when in 1962 my family moved from Melbourne to Brisbane when I was just five years old. I remember seeing Aboriginal people living under an open sky in Musgrave Park and asking an aunty, who were these black skinned people. None of my family, who were from country Victoria, had ever met an Aboriginal person. My Aunt’s reply was memorable, short and decisive. ‘We don’t talk about them.’

And that was the end of that. It was like she had waved a magic wand. From that point on, the Aboriginal people were there but I didn’t see them, even though I must have passed by the park regularly. My eyes could not see when there was no corresponding narrative or information. Silence bred a system-wide blindness towards Aboriginal people, their challenges, and their issues, and for me that veil of ignorance would not be lifted for nearly 15 years, when an enlightened professor at QUT- an American named Charles Adolf Dedeurwaerder – introduced students like me to the harsh realities in our midst.

And so it was that in 1980 as soon as I graduated from QUT. I headed for North Australia. Could it have been otherwise? I don’t think so. After several tumultuous years I returned to Brisbane for a short while before heading back to the remoter parts of the continent.

And it was in this in-between time that I felt a powerful need – like so many others – to fight against the unjust system, the entrenched racism, and all the rest of it. I saw art, writing, music and theatre as avenues for redress, and as luck would have it (and with encouragement from artist Eugene Carchesio) I found a sensitive and supportive community of artists at ‘One Flat’ to work with.

My undergraduate degree was in the Built Environment and I had some brilliant classmates, including John Willsteed (for a short while), Michael Ward, Michael Phillips, Andrew Wolter, and of course Eugene (with whom I would later hold two joint exhibitions – at the Schonell Theatre at UQ, and the Community Arts Centre in downtown Brisbane).

By the late 1970s I was already involved in the art scene, organizing social events at QUT with Xero, and The Humans, and other music groups. After returning from Mount Isa, there would be other, more adventurous gigs. ‘Raw Roar’ was one. It was a theatrical production at La Boite in which a loose collection of artists of all descriptions were invited to ‘roar’ on stage in their own unique ways (even silently).

Can you picture it? I recall Russell Lake and me and others, with heads bowed down, wandering aimlessly about the illuminated stage to the disquiet of audience members (and fellow performers) like choreographer Mark Ross. We were all over the place. It was complete chaos, but that was the point.

That’s how it was back then. That was the message. There were some startling performances by young artists from ‘One Flat’ who made us all think deeply about the human condition – especially one guy named Robert – and I wonder where he is now. ‘Raw Roar’ would not have been complete, of course, without Gerry Connolly doing his Joh Bjelke-Petersen impersonation, which was hilarious.

Then there was ‘Rogues and Liars,’ a performance that was to land a few of the ‘One Flat’ crew in a spot of trouble. On Australia Day (January 26) 1985, several of us (Adam Boyd, Genevieve Hopkins, Russell Lake and me) decided to disrupt the reenactment of the First Fleet landing at New Farm Park. We were confident that other protest groups would be there – the women’s groups, the socialists, and all the many others that Bjelke-Petersen had demonized – but we soon found that we were alone and no-one would be joining us.

The Big Aussie picnic by the river had attracted thousands of people and there was not a damn protester in sight. Where were they?

Fortified with a dose of tequila courtesy of Russell, we walked straight into the throng and down to the water’s edge. My knees must have been a tad shaky but the Rubicon had been crossed. There was no going back once we put on our t-shirts honouring the life and legacy of author Xavier Herbert, who had died a few months earlier.

In a radio interview I heard just before he passed away, Herbert had reminisced about the writing of his first book, ‘Black Velvet’ about the mistreatment of Aboriginal women in the Gulf country. His bitter critique of colonialism and of white supremacy spoke deeply to me, for I had just returned from the heart of darkness in North Queensland.

Herbert couldn’t find a publisher in Australia so he tried his luck in London and was told ‘We can’t publish this. There’s not one decent character in the whole book.’ Xavier replied, ‘That’s how it is in the Outback! They are all rogues and liars’. And that is what we painted in black ink on our white t-shirts.

In retrospect, I don’t know how we pulled it off. It was certainly a bold manoeuvre, but we looked to each other for courage as we walked arm in arm towards the boat chanting ‘Rogues and Liars’, and ‘Xavier Herbert Hates You!’

I recall the look of shock on the face of the young Captain Phillip as we tried to dislodge him, and I felt a bit sorry for the reveling picnickers. But there was no time for that. We had to think on our feet after our attempt to overturn the boat failed. Regrouping, we raced ahead and lay in the pathway of the oncoming military band, the big bass drum passing right over Adam Boyd (as seen in the press photos in the following days).

There were kicks and curses, and of course we were pounced upon by Bjelke’s troopers immediately afterwards. They demanded to know who we were working for and what cause we represented. I was still working for the Department of Aboriginal and Islanders Advancement [sic] at that time but our response was unanimous. We were artists on a mission! The ‘filth’ were nonplussed. It looked like we were going to be carted away until a few partying groups came to our aid – and I can still see them clearly in my mind’s eye. Gathering around and demanding our release were members of the Kite Flyers Association and also the Irish Scottish Association of Australia. The latter boldly spoke out on our behalf about how White Australia had a hell of a lot to answer for in their treatment of the First Australians, and the police let us go.

There is one final memory that I’d like to share from the early 1980s and that was the Bedroom Gallery that I created in the New Farm apartment that I shared with artists Adam Boyd and Russell Lake.

I had gathered various bits of artwork from ‘One Flat’ members and plastered them all over the walls and ceiling of my bedroom. (I still have examples from the art work. I put them in a ‘time capsule’ and hid it away). The one-night-only viewing was open to the public and it was a grand success though to say that the apartment was trashed was an understatement. Russell was away in Melbourne at the time and he is still cursing me 30 years on.

But I share this example because it shows the nature of the police state in which we were living. In the wee hours, long after everyone had left, there was a terrible thumping on the front door. I thought it might have been artist Zeliko Maric – what did he want? – and I begrudgingly went to open the door when it was forced open by three burly cops with bullet belts around their ankles.

I remember it clearly. They were brandishing badges and yelled something at me about illegal drugs on the premises. Pushing by me they encountered a naked Adam Boyd lying face down on the living room floor by the fireplace. Goodness knows what he’d been up to. They pounced on him – wanted to know if we were homosexuals (it would lead to a prison sentence in those days) – and then they started to ransack the place.

All that beautiful bedroom art became the topic of conversation of a most hateful kind. In ugly voices, they asked, what was this painting? What did it mean? Why did we have a picture of the mind-altering Datura plant on the wall? There wasn’t much chance of getting a word in, but I told them that they must have the wrong place, for at that exact moment, the people in the flat below were jumping out of the windows and scattering in all directions. The police followed in a mad rush, telling us to not move an inch. When they came back they arrested Adam and I photographed the whole thing, but that’s his story.

There is so much I could say about art and life back then; how our Schonell Theatre exhibition was threatened with a shut down on day one (Eugene and I had used a sculpted black garbage bag motif, with grass trimmings) or how the Courier Mail art critic of the day reckoned that what we did replicated work done so much better in Venice thirty years earlier, but it was all grist for the mill.

The early 1980s was a formative period in so many ways – creatively, emotionally and spiritually – and those many beautiful friendships are still bearing fruit, despite me living far away. The world has changed a lot since then, but the outrage continues. I am so thankful to have had the opportunity to live and learn alongside the special people at ‘One Flat’ who were dedicated not only to their art but also social justice and making the world a better place for us all.

You can view more about ‘One Flat’ here:

And a few photographs from my personal archives here:

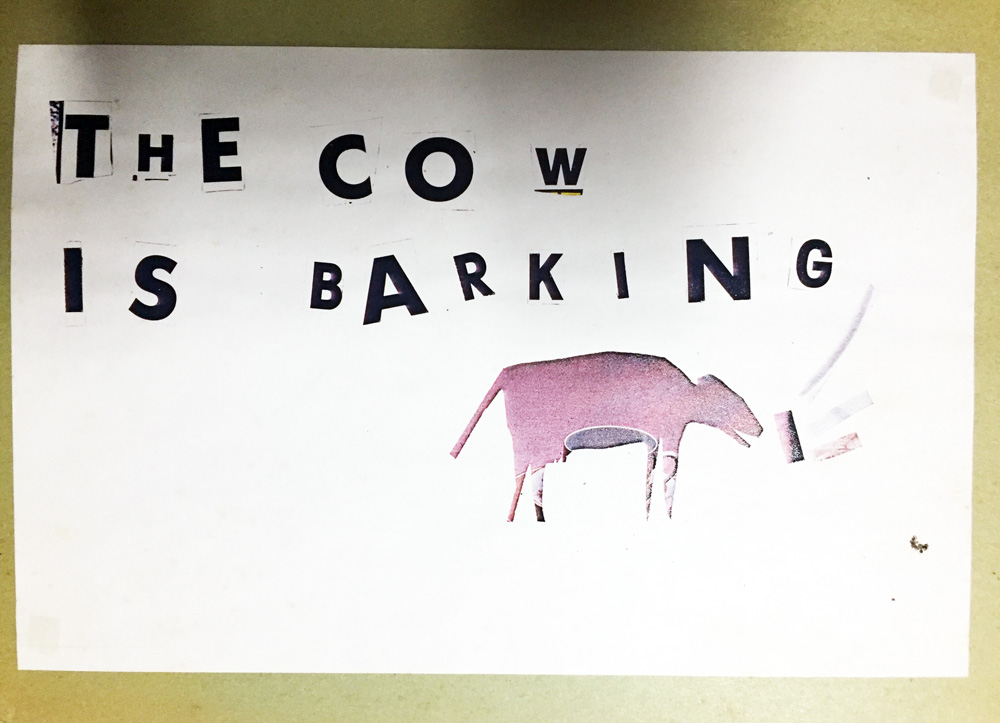

The Cow is Barking, artists Eugene Carchesio and Ian McIntosh “Bedroom Art” 1984

Schonell Theatre, artists Ian McIntosh and Eugene Carchesio

Schonell Theatre, artists Ian McIntosh and Eugene Carchesio