(Re) Presenting – Melbourne Art Book Fair Reflections – by artist Roberta Joy Rich – August 2020

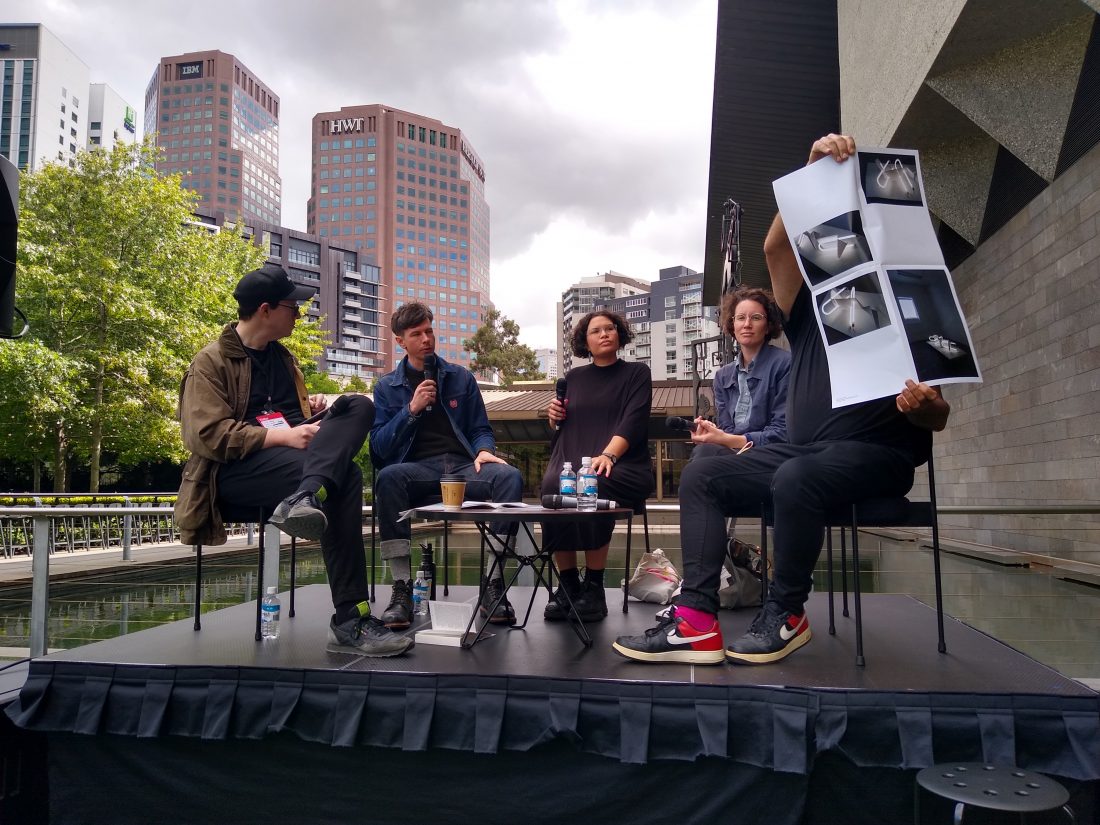

It’s grey, overcast, windy and borderline raining. It’s pre-COVID19 thinking. The sun I had felt that warmed my skin when leaving my house, has well and truly left. I am sitting outside the National Gallery of Victoria with Melissa, David and Paul in the NGV’s Grollo Equiset Garden. It is the PUBLIC RECORDS: ARTIST-RUN ARCHIVES IN AUSTRALIA panel discussion, as we share and discuss with Channon Goodwin, our projects and practices concerning forms of archives and how we each approach these in our art. We’re not thinking about how maybe it is inappropriate for such a gathering of more than 100 people at the NGV Book Fair, or maybe some of us were. This is in the back of my mind alongside feeling uncertainty and not really sure what the future holds, wishing I had dressed properly to not feel the cold.

Regardless, I met everyone for the first time that day and after listening to everyone’s extensive projects, from artist-run initiatives Cool Change, DAVID and ARI Remix, I felt privileged to meet, learn and share together about practice and discuss why and how we engage with archives. It was one of the last of a handful of public art events I went to that month, as the next day ‘Victoria’ would declare itself as a State of Emergency due to corona virus, and our first Lock down and closures of workplaces, schools and businesses would follow.

2020 has indeed erupted existing concerns, issues and social-political movements into the forefront of mainstream media, social platforms and people’s minds – some minds that bear the privilege to not have to even consider such frameworks of power and subjugation, let alone engage- where now more people of the globe are now surveying one another’s governance and environments (in both positive and negative ways), pooling finances and voices together, establishing unity among people, however through this battle it inevitably exacerbates hierarchies and continues forms of segregation.

From the devastation of land and peoples homes from the bush fires earlier this year, to the continued struggle of First Nation and Black lives in custody at the negligent hands of police and government authorities, the continued spread of COVID19 and its police management approach is evidently classist and racist in its treatment of affluent inner eastern suburbs people versus managing cases to those living in commission housing, and vulnerable low-social economic and working class suburbs in Narrm’s (Melbourne) south east, north and west areas. My heart aches for my family and friends in South Africa where current confirmed corona virus cases exceed 320,000, on top of an array of violent legacies that the Apartheid regime has left behind; while white landowners sit comfortably, South Africa’s diverse Brown and Black communities fight among each other and in complex ways together, to endure in these circumstances.

My intention was not to necessarily reflect on the time of now, but rather reflect on the Melbourne Art Book Fair panel discussion, but while writing this, I think the expression of my bleakness is an extension of a memory I have from the conclusion of the panel that was somewhat bleak and frustrating. What reoccurs in my mind from that day, is not just the ambitious and complex works that the panel spoke of within the drab grey setting, but the questioning that would come afterwards by an audience member, who rather than ask further about aspects of our work and approaches to practice, felt it necessary to make it known that they didn’t feel what we were doing was worthy of being classified as a form of art making, or rather challenged our integrity.

The conversation began with others on the panel with this person, as I reconvened, coming in part way through the discussion, that involved us sharing further why we do the work we do and the significance of this work in order to represent the practices of our communities and our experiences. I remember being mind blown that this person just continued to speak and listen to themselves and their definition of what practice and artistic integrity meant for them, as they felt the need to continually elaborate this to us, as if we were in need of ‘saving.’ At one point, I didn’t even understand what they were trying to say exactly, as they became more convoluted; I remember expressing that for some of us, the centering of Western artists, problematic arts ‘movements’ and the pedagogy of arts education was not sufficient or relatable to our realities, where art making, production and critique that was relatable, had already been occurring, however was not regarded nor centered to the Western trajectory of time and production that centres only their lives. I made this point to express to them that the work that we are all doing is to enable us to re-imagine or re-envision an archive and its relationship with contemporary arts practice and what that could mean for us; negating Western imperialist art practices and euro-centric expectations.

I briefly met Paul Andrew in the NGV Foyer prior to the panel discussion and following events. Andrew complemented my ‘anarchiving’ efforts in my recent exhibition WE KOPPEL, WE DALA held at Metro Arts in Brisbane last year. The exhibition presented video works ‘Remembering District Six’ and ‘M/other Land’, two works that present ideas of reclamation and re-visit sites of loss, through performance and video. If you have been to Metro Arts, you would be familiar with its unique architecture, and thick dominant pillars that intersect its interior. Adjacent to these pillars, I had positioned vitrine installations, theatre lit with red light, and one with purple hues. Each held evidence of the legacies of Apartheid government policy and research, including a Dom Pass and a cartography study, an ‘atlas’ filled reports regarding age, gender, race, occupation, religion and more, meticulously mapping where all of these signifying traits resided in the city of Cape Town. Nearby, a 1 Rand coin – old Apartheid money – bears the head of one of its instigators, Hendrick Verwoerd. The installation presents the coin positioned upside down inside the red-lit vitrine. It was my way as someone of the diaspora to tell my story within a colonial context that directly influenced Apartheid law, to share that this shit was and is real, and create a space to reflect upon this; for those affected by these histories, and how these ideas continue to resonate in the settler nation Australia context.

Though we were all supportive of one another in discussion, I think we eventually were all rather exhausted by this interaction as they had extracted enough emotional labour from descendants of the people whose ancestors and cultures birthed the expropriated aesthetics and practices that have come to influence and benefit the so called pinnacle of Western modern art and Western exploitation of Bla(c)k art (Klee, Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, Gauguin for example, or see Richard Bell’s ‘Bell’s Theorem: Aboriginal Art—It’s a White Thing!).

And so this moment, though bleak and frustrating for me, demonstrates the need for critical, compelling and perhaps ‘unconventional’ arts practices to continue to occur from Bla(c)k, Queer and POC artist communities of all abilities alike. We need to continue challenging an understanding of art, inscribing our truths into the world, mirroring the society we see and stoking the cultural molotovs that will usher in their irrelevancy.

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/program/panel-discussion-public-records-artist-run-archives-in-australia

Roberta Rich is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work responds to constructions of identity and historical archives, often referencing her diaspora southern African identity and experiences. Rich has exhibited projects at Blak Dot Gallery, Melbourne (2017), Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg (2017), Footscray Community Arts Centre (2017), Arts House (2018), Gallery MOMO Cape Town, (2018), FELTspace, Adelaide (2018), Firstdraft Sydney (2019) and Metro Arts, Brisbane (2019). Her residencies in South Africa were supported by NAVA’s Freedman Foundation Travelling Scholarship and is the 2020 recipient of Australia Council for the Arts Debra Porch Award.

https://metroarts.com.au/we-koppel-we-dala

Images by Louis Lim taken of Roberta’s solo exhibition, WE KOPPEL, WE DALA at Metro Arts, Brisbane 2019. Images show the interior of a darkened gallery space with vitrine installations lit with red theatre lighting, showcasing artefacts and the gallery walls display video artworks and projections.

WE KOPPEL, WE DALA

Metro Arts Brisbane 26 June – 13 July 2019

Photo: Louis Lim

WE KOPPEL, WE DALA

Metro Arts Brisbane 26 June – 13 July 2019

Photo: Louis Lim

WE KOPPEL, WE DALA

Metro Arts Brisbane 26 June – 13 July 2019

Photo: Louis Lim