Interview with Adam BOYD and Virginia BARRATT

the ephemera interviews

In this series of interviews artists directly involved in ARIs and artist-run culture 1980- 2000 speak about the social context for their art making and provide insights into the ephemera they produced or collaborated on during this period. Artist ephemera includes artworks, photocopies, photographs, videos, films, audio, mail art, posters, exhibition invites, flyers, buttons and badges, exhibition catalogues, didactics, room sheets, artist publications, analogue to digital resources and artist files.

November 11, 2015

PA:

Adam, Virginia Hi and thanks for your overview today, tell me about your motivations for starting the artist-run John Mills National located at 40 Charlotte Street, Brisbane in 1986?

AB:

We wanted to create a dedicated space for performance and installation. Exhibition venues were available to younger artists, not in great numbers but they existed. The early eighties were a time when performance and installation became viable forms of expression within an otherwise very traditional and conservative arts culture.

One Flat and A Room were particularly important in seeding the idea that art practices were rapidly changing. It took many years for the dominance of painting to fade (late 90’s?) but at the time of JMN, there was still a great deal to be done to claim the ground needed for the popular acceptance of performance and installation as primary practices.

We felt that a dedicated space for those modes was needed, so when the opportunity to take over the lease of the JMN building came up, we took it. In the back of our minds though, was the knowledge that it would simply be an exciting project, a great place to hang out with like minded people, and despite the understanding that we would be largely ignored by the establishment it would be an important step towards cultural transformation.

The John Mills Himself has a vibrant artist-run history from 1982-1987. The Entrepot collective of QUT architecture students moved into the rear studios of the John Mills Himself building in 1982, co-ordinated Mark Thomson this building in turn became a co-working space for 40 architecture students, artists, writers, designers and live music, a lively inner city creative precinct during the oppressive Bjelke Peterson regime when many heritage listed or potential heritage listed building were being demolished.

The John Mills Himself has a vibrant artist-run history from 1982-1987. The Entrepot collective of QUT architecture students moved into the rear studios of the John Mills Himself building in 1982, co-ordinated Mark Thomson this building in turn became a co-working space for 40 architecture students, artists, writers, designers and live music, a lively inner city creative precinct during the oppressive Bjelke Peterson regime when many heritage listed or potential heritage listed building were being demolished.

VB:

I had come from a performance background, in theatre (I had studied drama at the DDIAE in Toowoomba, which is where a surprising number of artists involved in the 1980 artist-run scene also studied), which I found stultifying and which wasn’t suited to my sense of alienation!

I was excited by the performative work that was emerging from the Brisbane subculture of clubs, live music, fashion houses, studio spaces and the generative crossovers that were created via this countercultural carving-out-of-space.

I spent most of my week nights dancing in the valley or in the city and was doing performance with Michelle Andringa, and teaching movement classes and singing with Michelle Andringa which was such a joy.

Adam had been working with One Flat, and Michelle and I went along as video singing heads (to the song “don’t fence me in”, I believe) on their 1986 O’FLATE National Art Safari.

In 1986, artist Wendy Mills who had been living in the street level studio of the John Mills Himself building (there were in fact two Wendy Mills’ in the building), moved out and the lease was up for grabs. We grabbed it, with the idea of creating a space with a primary focus on performance.

It was a great building, already housing architecture students, artists and rabble rousers. It was a building I had spent a lot of time in over the 1980s – singing, rehearsing, dancing, filming with Brendan Smith, Anna Zsoldos, Michelle Andringa, Jewel Palace and many more art students and anti-fashionistas.

Taking over the ground floor space in the John Mills Himself building meant that we were aligning ourselves with a political push to create culture that was resistant to the reigning art establishment, the political climate and the psychogeography of a regional town on the brink of great change.

Performance (on the streets, or off, on the walls or off), was a perfect vehicle for fucking shit up, pretty much, for fuck art, let’s dance (and for that dance to BE art). It was also a great venue and space for experimentation, for me, in particular, to work through processes around what a feminist art + performance practise might look like.

AB:

In retrospect I think events take on more of a political hue than they had at the time or maybe it’s just that one doesn’t always see the political in their actions… but at the time, for me, JMN was mainly about creating a space where everyone could come to gather with all their baggage and their different perspectives and we really wanted to celebrate that. Celebrate those differences.

Personally I didn’t want to align myself with ‘political’ art. That sort of work always seemed too obvious and didactic.

We invested so much energy in resisting singularities anyway, so it would have been ridiculous to be overtly political by design. The real fight, if you can call it that, was with the institutions who called on us to be passive, to be consumers, to be complicit in THEIR project.

Well we said fuck that. We got other ideas so thanks, but no thanks. We talk a lot about the drugs in those days, but the big high was really in occupying city spaces as the ultimate act of demystifying corporate power. We were lucky enough to have the means to take over the city while it’s gaze was elsewhere.

In terms of the politics of space and preserving architectural heritage, we were the band that played while the Titanic went down. Afterwards I guess we just floated away on our instruments.

PA:

What was your JMN mission statement (for want of a less hideous term)?

AB:

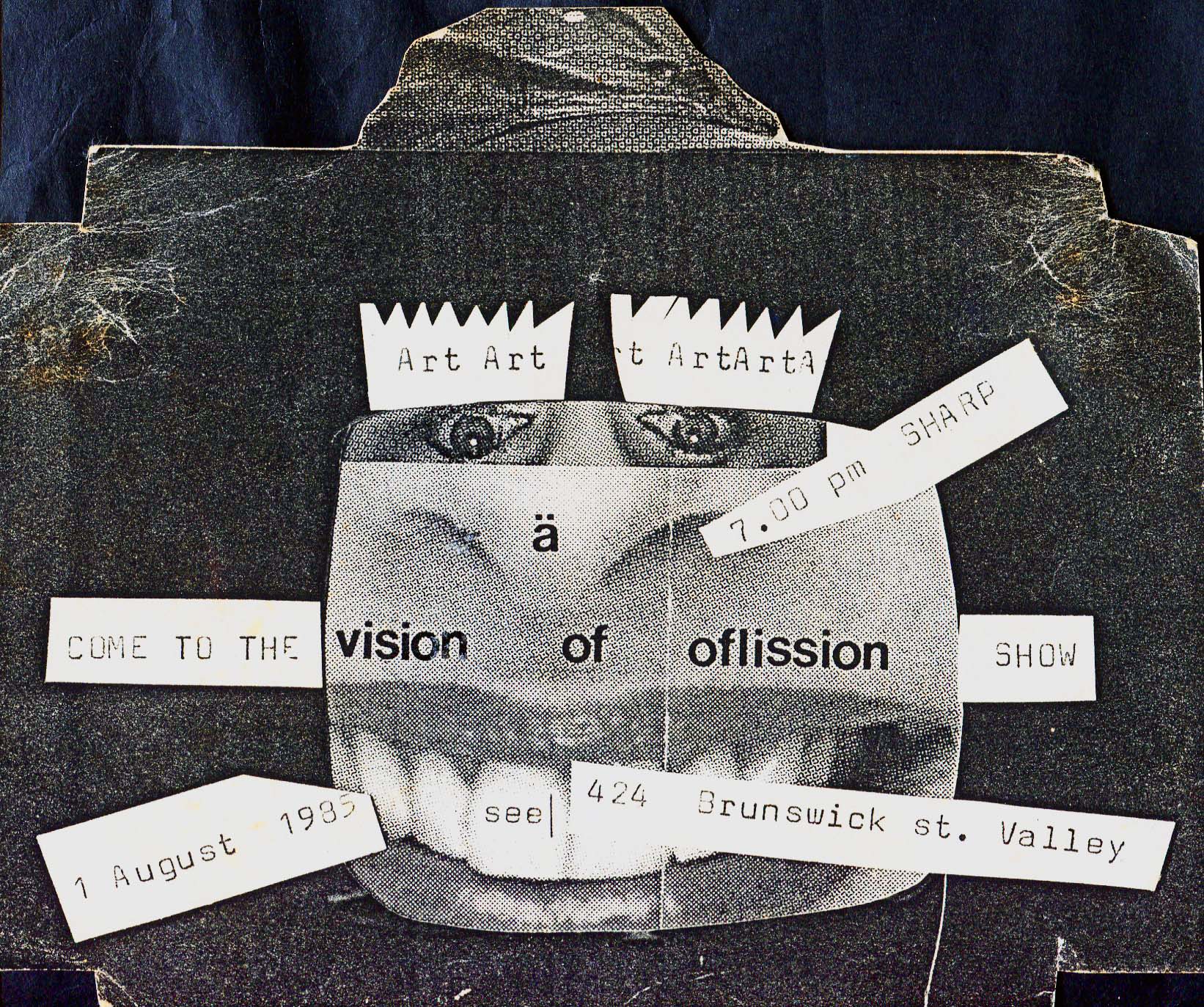

To create a flexible, reflexive, loosely structured venue for the support of installation, performance and other experimental art practices. We welcomed interstate and international participation and collaboration and were available for any viable and interesting project. Except vivisection and snuff films. We had a real strict policy on that. I mean, you’ve got to draw the line somewhere.

VB:

Ha ha. The lines were without limit, in a sense, since we opened the door to pretty much everything that came our way, loved spontaneity and experimentation, preferred works off the walls, incendiary and participatory. I don’t recall any ethical dilemmas.

AB:

Excluding our personal ethical deficiencies that is. Well, I can only speak for myself here…

PA:

Describe the operational model you used. Fold in examples of how particular artists met those goals?

AB:

The approach we took was to be open and available to everyone and anyone who walked in the door. Whether an artist was ‘experimenting’ with installation/performance, or they were core modalities for them, it made no difference. We were there to support and encourage them.

Occasionally artists would come in peddling conventional painting, drawing etc and we gently pushed them out the door. But it wasn’t common. We were trying to build critical mass around experimental practices more broadly.This is why we programmed so much activity.

Also, we knew that the first two weeks of an exhibition was the time when most visitors came through and that after two weeks very little would happen. So we kept the exhibition dates shorter to allow us to hold more exhibitions and more performance events.

We also encouraged artists working materially on the walls and in the space to consider performance on the opening night of the show, and in the intervals between exhibitions when we held performance events.

The JMN Annexe, a small street window space, had a high rotation too and was offered to exhibiting artists first. Most, if not all, took the opportunity up. It gave the space 24 hr potential, and in the process pipped Avago as the smallest exhibition venue in the country. Ha ha!

VB:

Oh! I also failed to mention our own branding. John Mills National was clearly a swipe at the hierarchy of “flagship” artspaces, and their operational models of directorship and curatorial practise. This was a device used in a lot of culture hacking projects – co-opting the language and practises of the overlords, the gatekeepers to “culture” and turning the lens back onto the inequities in that system.

This device I think was integral to our operational modality which was very much NOT based on curating for excellence and consistency, since we showed artists who had never-before exhibited across a variety of media as well as accomplished practitioners.

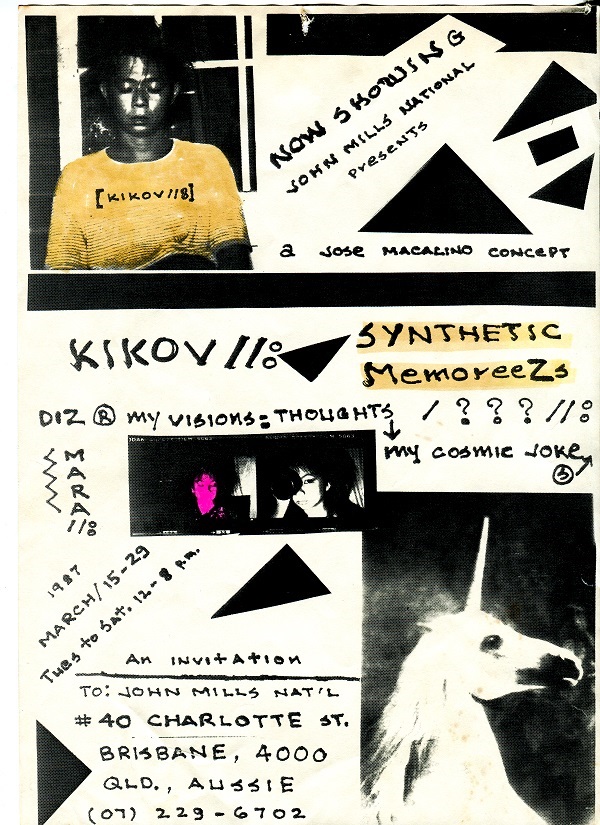

We had an open door policy, and a policy of making things possible, and did our best to accommodate whatever might arise on the spot. Fiona Templeton’s performance was an example of this, as was the one-line sculptural carving of Ken Hiratsuka on the front steps of JMN.

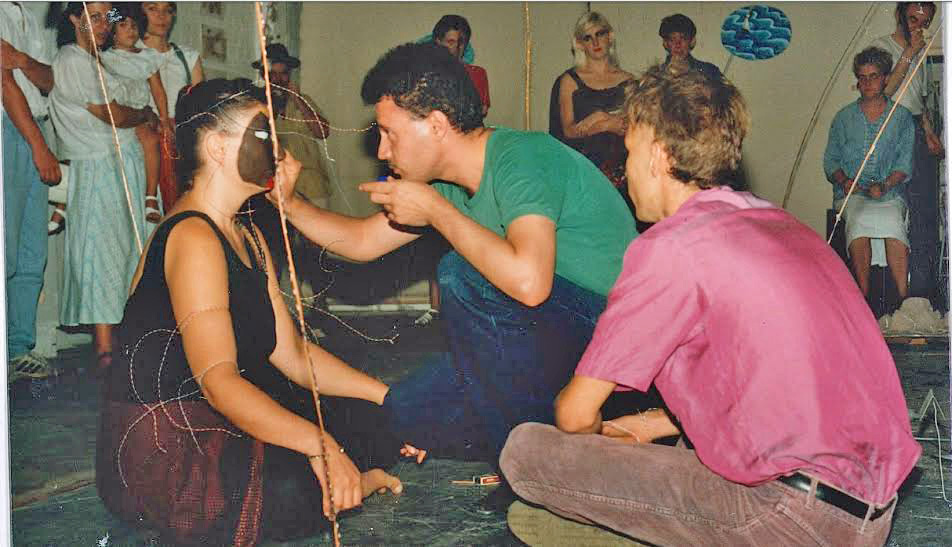

I think audiences quickly learned that anything could happen in the JMN space, and often people watched from outside through the windows if there was the threat/promise of a little too much audience participation (Joey Macalino, VB and axes etc).

We also invited submissions for events, and became very quickly known as the space for performative works, or being a space where an artist might exhibit an experimental body of work that deviated from their normal practice.

In this way we were very much process-based. We had a lot of wall works as well, usually accompanied by opening night or closing night or mid-season performances.

AB:

That’s right. Ken and Fiona’s performances were great examples of how we could respond to opportunities quickly and not get bogged down in planning, programming and procedure.

We had a very strong tendency to say yes. And if anyone exemplified the idea of artists wholeheartedly engaging the opportunity to take the stage it was Joey Macalino’s unashamed, unapologetic, hopelessly romantic sprawling, chaotic performances.

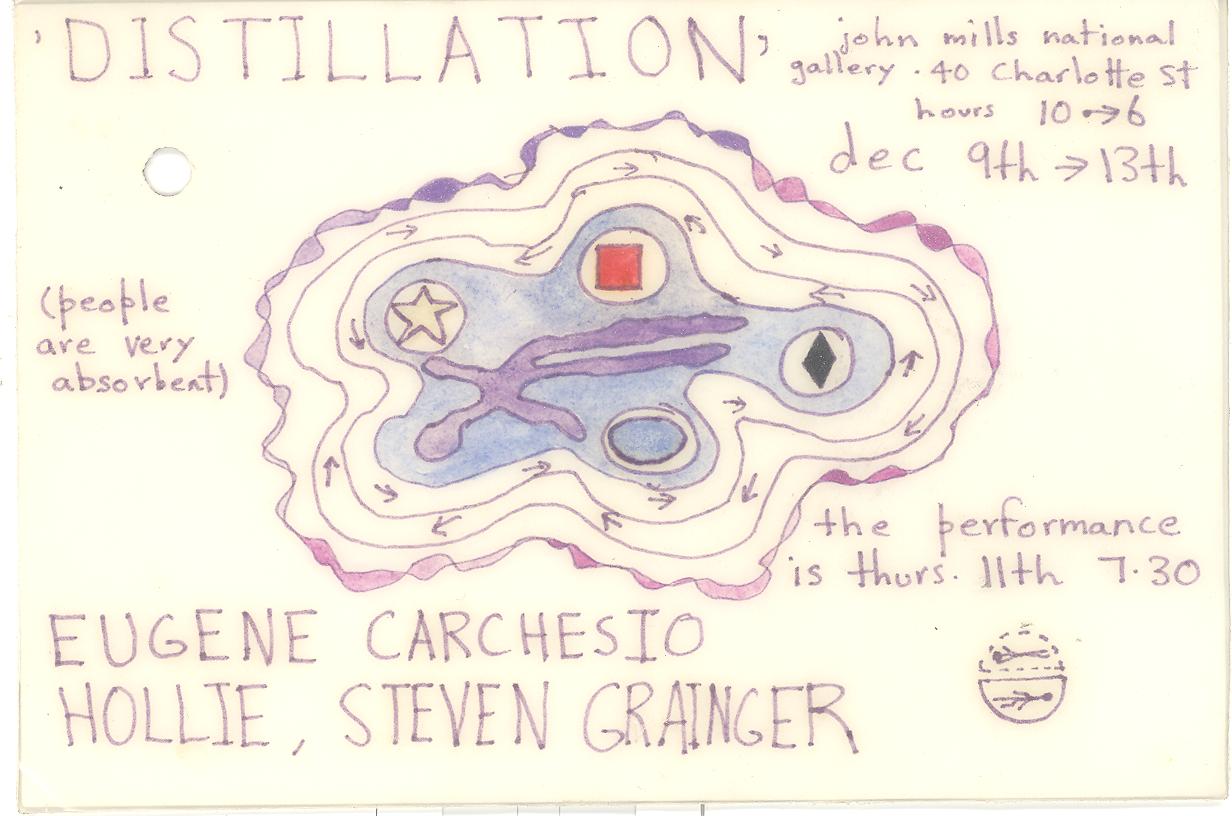

Then there were people like Mal Enright and Cernak, who had strong, established practices of their own and who rose to the challenge of installation practice in powerful ways. Adam Wolter, Eugene Carchesio and Steven Grainger could always be relied on to be great contributors too, whatever was happening