Stranded Doing the Strand – Artist Luke Roberts

By Luke Roberts

OPEN Letter to Brian Doherty @ ARI REMIX

Whilst this is a response to your request Brian for a single word that might sum up ARIs in 1980s Brisbane, you’ll read that I’m responding in a more extended way to the question. I ask the reader to at least try to understand why this era still rattles me after all these years.

STRANDED is the word that comes to mind, a loaded 1970s word to be using for latter day (read 1980s) Queensland organisations (read Artist Run Initiatives/ARIs). There are a number of reasons for me to suggest this word, some obvious, others maybe not so and some also contentious. We certainly were quite ISOLATED at that time in Queensland, both geographically and politically. The recent documentary on ABC about the groundbreaking punk band, The Saints gave a condensed and reasonably accurate account of the awful political situation in Queensland in the 1970s and 1980s.

It rattled the cages of the past, awakening ‘demons’ and put much into perspective, for me at least. In its way it was a kind of exorcism not only rattling, but also opening cage doors and giving much-needed acknowledgement of how things were. Recognition of horror goes a long way to healing post-traumatic stress disorder. It would be instructive to all of us to view this documentary and be reminded, and for those who weren’t here to be given a quick lesson in Queensland’s recent ugly past and be appalled.

Livin’ in a world insane

They cut out some heart and some brain

Been filling it up with dirt

Yeah baby dunno how it hurtsTo be stranded on your own

Stranded far from home, all right*

It was focused, understandably, on a particular subject, namely The Saints. However in describing the terrible background The Saints came out of it gave little indication of the suppression that minorities in Queensland were subjected to and presented the general state of affairs as a somewhat heteronormative left against a rigidly heterocentric, fascist regime. In this respect I’m reminded that despite the perceived leaps forward there is much that remains in place. Consider the current attitudes of the likes of Cory Bernardi and the Christian Lobby and their efforts to stop funding to protect GLBTQ and other teenagers from bullying at high school.

The concentration on the 1980s ARIs in this forum may result in part from the upcoming UQAM exhibition and simply underlines a certain weighting. (I appreciate that ARI Remix plans to extend its scope from 1980 to 2000 and is welcoming in its embrace. The greater input currently deals with the 1980 – 1990 and I am responding to your request Brian for a word that might sum up the 80s ARIs.)

STRANDED. Yes there were gay (GLBTQI) individuals that were involved in the ARIs of the 1980s here in Brisbane, but where were the overt political works? Where were the visible art protests? Perhaps they did exist and I’m simply unaware of them. No offence intended to Virginia, Paul, Hiram etc. Where were the Aboriginal artists in these 1980 ARIs? I’m aware that at least one ARI artist (Jeanelle Hurst) was involved in a street march and I’m keen to hear what other kinds of political works came out of the ARIs. One can ask, “Do ARIs have to be politically focused?” or is it a case of “Keep calm and carry on”? **

I left Brisbane in early 1984 in self-imposed exile and returned in late 1987. Effectively I was away for four years. I’ll admit that I couldn’t possible know all of what went on in those four years. However I did return to a certain status quo though the winds of change were palpable. Brisbane had grown up to some degree. The much-loathed Bjelke-Petersen regime had finally been disgraced and was on it way out. A new energy was apparent in the artworld here. This was in part due to the ARIs and the fact that the eyes of the world were looking towards Brisbane and Australia with the upcoming Expo88. Terms such as “post-modernism” were in lavish usage and the Aboriginal renaissance was well and truly visible. Women’s rights were also being acknowledged and demanded. There were signs of a Matriarchy developing in Brisbane and using pejorative terms such as ‘gay mafia’. I can name the Brisbane matriarchs of the time, but I’m still puzzled by who the Gay Mafioso were. No doubt I was considered one of them (read ‘One of Them’).

Gay and Queer politics were given a flowering in the 1990s and then packed away as a kind of ‘been-there-done-that-lets-move-on’. ‘The Queers have had their moment in the sun’.

I realise that this is a venting of sorts. The trials of the past are conjured up by these memories and events. We were all affected by the horrors of that time, but I ask, “Were there laws in place specifically aimed at denying and denigrating your sexuality and also new ones devised in the 1980s?” Not only was it illegal to be gay, have gay sex, cross-dress*** in Queensland, but also in 1985 the Bjelke-Petersen government passed an atrocious, homophobic amendment to the Liquor Act known as the Deviant Law. Most people don’t remember the fact or weren’t even aware of it. Care Factor Nil I suppose, if one wasn’t affected. It is also relevant to mention the World Health Organisation listed homosexuality as a mental illness to be eradicated and only removed from its books in 1990. The Bjelke-Petersen regime and its police henchmen were obsessed with homosexuality and those other pinkos the unionists and communist reds.

Post the Bjelke-Petersen era, in the 1990s, I was wrongly accused by a member of the artworld as presenting as a victim. This writing isn’t about outlining hierarchies of suffering, which I don’t believe in anyway or an attempt to establish a victimhood status. We all suffered. I’m not sure how much it is appreciated that when anyone is discriminated against we all suffer. I simply want to remind the reader that this was an ugly era in Queensland politics and a disgrace to Australia in general. It was not, from my perspective, a period that I have many particularly pleasant thoughts about. I felt my youth and my dreams and those of my friends and any young Queenslander were sacrificed to the political expediency of a grotesquely provincial experiment in fascism.

The specific dates of the upcoming UQAM ARI show simply underlines for me and others, the ‘perceived indifference’ and lack of understanding of what openly gay (LGBTQI) artists have had to deal with. By locating the scope of the exhibition between the Commonwealth Games of 1982 and Expo 88 the openly queer ARIs of E.M.U (1979-1981) and AGLASSOFWATER (1988 – 1992) are effectively sidelined. I understand these ARIs may be given a mention in the catalogue. This is not to be seen as an attack on the curator Peter (Anderson) either, but simply pointing out that the choice of dates can be perceived as a convenient decision about a heavily politicized era and could be interpreted as an example of the sidelining, editing and Totschweigetaktik**** that still dogs the tracks of LGBTQI history here and continues to leave us STRANDED.

Naturally I’m encouraged that there is a concerted interest in recording the achievements and struggles of that controversial time. I give particular acknowledgement to Paul (Andrew) here and his Trojan Horse efforts in documenting the ARIs and bringing the existing wealth of peoples’ voices and archives into the public arena. Nonetheless it still remains a period of history that is difficult for me to revisit.

Even though I attempted to seek political asylum in the Netherlands in the 1980s I returned to Queensland. Queensland after all wasn’t a country, despite Bjelke-Petersen’s threats to secede. Early on in the 1970s HDH Pope Alice had seceded from Brisbane and ‘cordoned off’ a section of the city proclaiming it Vitanza City after the tyre service in the Old Rivoli Theatre in New Farm. This conceptual gesture was neither enough to sustain me nor give me a sense of security. I sold my shop and house and travelled as far away from Brisbane as I could go, to “the Port of Amsterdam, where the sailors all meet”.***** Before reaching the Netherlands I spent time in Tokyo, London, Ireland, Paris and Germany.

I was determined to stay away for at least two years and had a desire never to return. I’d only been out of the country once before on a two-week holiday and the prospect of surviving the other side of the world was a little daunting. Others had done it before so why not me. Brisbane had not given me the proper professional grounding that I required as an artist. Despite having had a solo show at the Institute of Modern Art in 1982, which was a rare event for a Queenslander then, when I approached the Australia Council two years into my time away, they didn’t know who I was and subsequently I didn’t receive a grant. I know this as a member of the Australia Council told me when I returned to Australia. Queensland has had a rocky relationship with the Australia Council and its funding program. The evidence would be there on their records. Queensland was the “poor relation” and at that time the laughing stock of the rest of Australia, except in Tasmania where they thought Joh was some kind of peanut god.

It was liberating to be the other side of the world in other cultures and countries. I ran my house on the top floors of an old clock factory in Monikenstraat in Amsterdam’s Red Light District somewhat as an ARI. I exhibited my work there and that of others and held events. I also exhibited in other unconventional space around the city and did eventually come to the notice of art dealers. My first public exhibition ‘Name Dropping’ was in a space opposite Central Station. Towards the end of my time in Amsterdam I exhibited ‘Plan 9’ at the advertising business Compartners on one of the canals. ‘Plan 9’ took its title from ‘Plan 9 from Outer Space’, a Golden Turkey of a film that some of you would be familiar with. I worked with other artists and led as Bohemian a life as my need to earn a living allowed.

I was what was known as a ‘black worker’ and washed dishes and cooked in a restaurant to keep body and heart together. I was illegal in that I’d overstayed my visa and could have been deported at anytime. However the Netherlands, more than other countries, had a more lenient approach. Nonetheless there were regular deportations.

There were times that I wished Queensland was a country so that I could’ve hoped to achieve political asylum in my new home. Support for South Africa was growing and Bjelke-Petersen and his regime were not given favourable press in Europe. One of my artworks of the time was a cartoon of two semi-abstract figures talking. One said, “Joh was a country remember”. The other replied, “Yes, we remember.” Ba Boom! After all the National Party had once been the Country Party.

I however remember my great delight in seeing the Go-Betweens and their ‘Spring Hill Fair’ being listed as upcoming events when I visited Hamburg. Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds were the favourites of Berlin and Leigh Bowery was creating his legend in London.

Fifi L’Amour and David DeMost moved to Amsterdam during my time there. They performed in Berlin for the 750th Anniversary of Berlin. I travelled there with them and met my hero Nina Hagen as I had backstage access being involved with Fifi’s wardrobe and a friend of mine did their make-up. That friend Lesley Vanderwalt is currently a nominee for this year’s Oscar for make-up. Yes, name dropping again.

After four years away I was looking to move from Amsterdam to what might be greener pastures. Barcelona was in my sights. It was a fascinating city and Spain was throwing off the shackles of its own extended period of fascism. I didn’t have much by way of savings and would be looking for accommodation and a job in a place where I didn’t speak the language. I could also see that if I were to remain in Europe I would have to become a ‘European’ artist. Australia meanwhile was blossoming and much to my surprise even the young French wanted to travel to Australia.

From day one in Paris it was obvious that Australia had become branché. Backpacks in the shape of koalas were everywhere; Aboriginal Art and golden beaches had opened up the eyes of the Europeans to a new world down under.

Reports were coming in that the horrors of the Bjelke-Petersen era were ending and the jig was up for the National Party. I decided to return to metaphorically knit like a latter-day Madame Defarge as heads rolled. I had to return to make sure I hadn’t nightmared (sic) it all up. It was imperative for me to go through the necessary processes at ground zero to unburden myself. I’m still doing that. It is grist for my creative mill after all, whether I want it to be or not. I had seriously considered suing the National Party for mental anguish. Their spin-doctors would have had a great time with that idea.

Yes, we can hear the violins playing and we can either put lipstick on the pig that was that socio-political environment of that time or attempt to tell it like it was and achieve some healing and truly move on. I’ve set up strategies to avoid being continually enthralled with the hypnotic lure of painful emotions, past events, and any worries about the future. At heart I’m an optimist. I appreciate that happiness is a decision. However I’m also an historian with a belief that we can only really move on by acknowledging. My work has centered on hidden histories as much as anything else. We currently live in a world operating around great lies where the truth is marginalized and that which doesn’t suit the Agenda is also marginalized and the marginalized are in turn used to consolidate the Agenda.

Marginalisation was forced upon me at birth. Of course I didn’t realize it at the time, but its ugly shape began to be seen way before I even recognized it for what it was. I have taken it upon myself as a badge of honour, a raison d’être for my very existence. I am an activist for the marginalized. I understand that most of us feel we don’t belong. I however was told in no uncertain terms from a young age that I didn’t and don’t belong.

The ARIs of the 1980s were admirable in that they happened at all, given the great cultural indifference that Queensland has for almost anything of its own. Whilst so much has come out of Queensland there remains an atmosphere of ‘nothing to see here. Keep moving’, ‘nothing happened’ or at least ‘nothing good happened or happens’. On the other hand however, as a detective in Andrew McGahan’s Last Drinks noted, Queensland will bend over for anyone or anything from the outside world.

For the show ‘One Square Mile’ featuring Brisbane’s minorities, which Michele (Helmrich) co-curated for the opening of the Museum of Brisbane I produced a series of postcards with witness statements on the back. This was yet another attempt to establish my own history and that of my peers. Richard Bell, who co-curated the exhibition, said to me he’d rather be born aboriginal than gay and freely admitted that he was a recovering homophobe. Richard added clarification when I recently asked permission to quote him. “I said that in the context of the situation in the 1970s Joh era with the rampant gay bashings. It was a harrowing time for many, many people but during that time I thought the cops hated gays more than they hated us blackfellas.” *******

I still feel somewhat alone in endeavour to establish my story and that of others. Despite my achievements and being included in shows like ‘One Square Mile’, there remains that strong sense of ‘death by silence’ (Totschweigetaktik). Perhaps this void can never be filled for any of us. Do we ever have a sense that our story has been fully told? These days I’m far more at peace with myself and my communities than I ever was as a youth. Have I settled for less or is it simply that after spending several extended periods of time in the outside world Brisbane has more pluses than minuses for the moment.

Now that the past has ‘safely’ gone we often have a distorted view of it and make it more grandiose than it was, perhaps even more terrible than it was, change the emphasis, and even change the goalposts.

We turn it into mythology. In its own way it also becomes STRANDED. The older we become the greater the heroes we were in our youth. Because there wasn’t enough published writing and other serious witnessing in film and photography at the time we forget detail and see it through the lens of the present. We may even imagine we had mobile phones back then. However some things were very real.

In closing I’ll add these extracts from Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LGBT_rights_in_Queensland

“While other states in Australia began to liberalise their anti-homosexuality laws in the 1970s and 1980s, Queensland was ruled by the socially conservative National Party of Joh Bjelke-Petersen.[4] His government refused to countenance changes to the law, describing gay people as “child molesters” and “perverts”.[4] At this time government policy was hostile; the Education Department refused to hire the openly gay teaching graduate Greg Weir and in 1985 the government passed an amendment to the Liquor Act making it an offence for publicans to serve alcohol to “perverts, deviants, child molesters and drug users” or to allow them to remain on licensed premises.[4] The anti-homosexuality laws were enforced by police throughout the 1980s, including against men who were in same-sex relationships and were not aware that their private conduct was illegal.[4]

…The Fitzgerald Inquiry was commissioned in the late 1980s in Bjelke-Petersen’s temporary absence, following allegations of corruption and misconduct in the Queensland Police. The inquiry subsequently investigated the entire system of government. One of its recommendations was that a newly established Criminal Justice Commission review the laws governing voluntary sexual behaviour, including homosexual activity.[7]

This proposal was an issue in the 1989 state election. National Party leader Russell Cooper, whose party was heavily implicated in corruption by the Fitzgerald Inquiry, tried to galvanise socially conservative support using his party’s opposition to the legalisation of homosexual conduct. During the election campaign he claimed that his party’s corruption was a “secondary issue” to moral issues like abortion and homosexuality, adding that the then-Opposition ALP’s policy of decriminalisation would send a “flood of gays crossing the border from the Southern states”.[8] These advertisements were satirised by Labor ads depicting Cooper as a wild-eyed reactionary and a clone of Bjelke-Petersen and/or a puppet of Nationals party president Sir Robert Sparkes.[9] Cooper’s party was defeated in the election.

…Goss’ government largely implemented the changes in the Criminal Code and Another Act Amendment Act 1990, which was passed by the parliament on 29 November 1990.[4] However, a truly equal age of consent was not implemented. Queensland’s age of consent is 16 for oral and vaginal sex. By contrast, anal intercourse, or “sodomy”, involving any person aged under 18, whether male or female, is a criminal offence, punishable with up to 14 years imprisonment.[11] Patterson described this as a “pragmatic political response” to the objections of religious lobby groups, who largely equated homosexuality with sodomy.[12]

Footnotes:

* The Saints, (I’m) Stranded, lyrics written and composed by Chris Bailey and Ed Kueper, (1977).

** “Keep calm and carry on”, a motivational poster produced by the British Government during World War II.

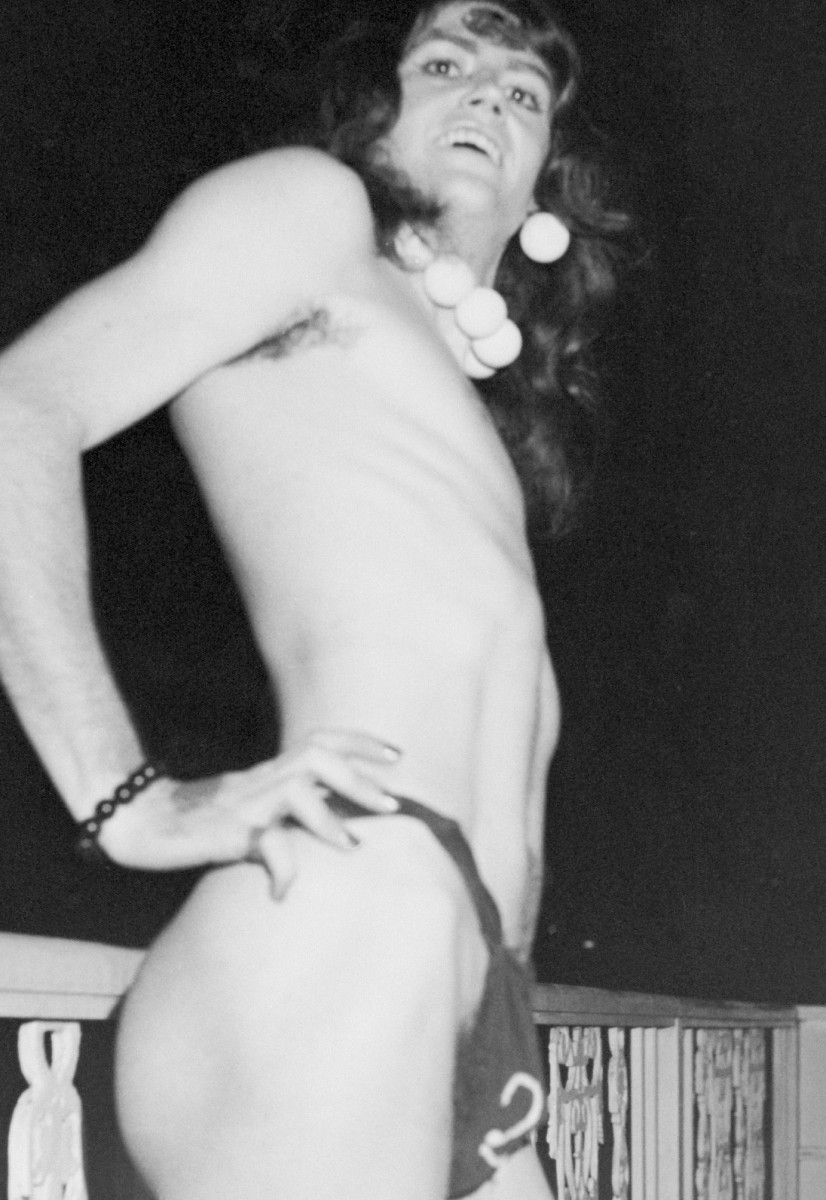

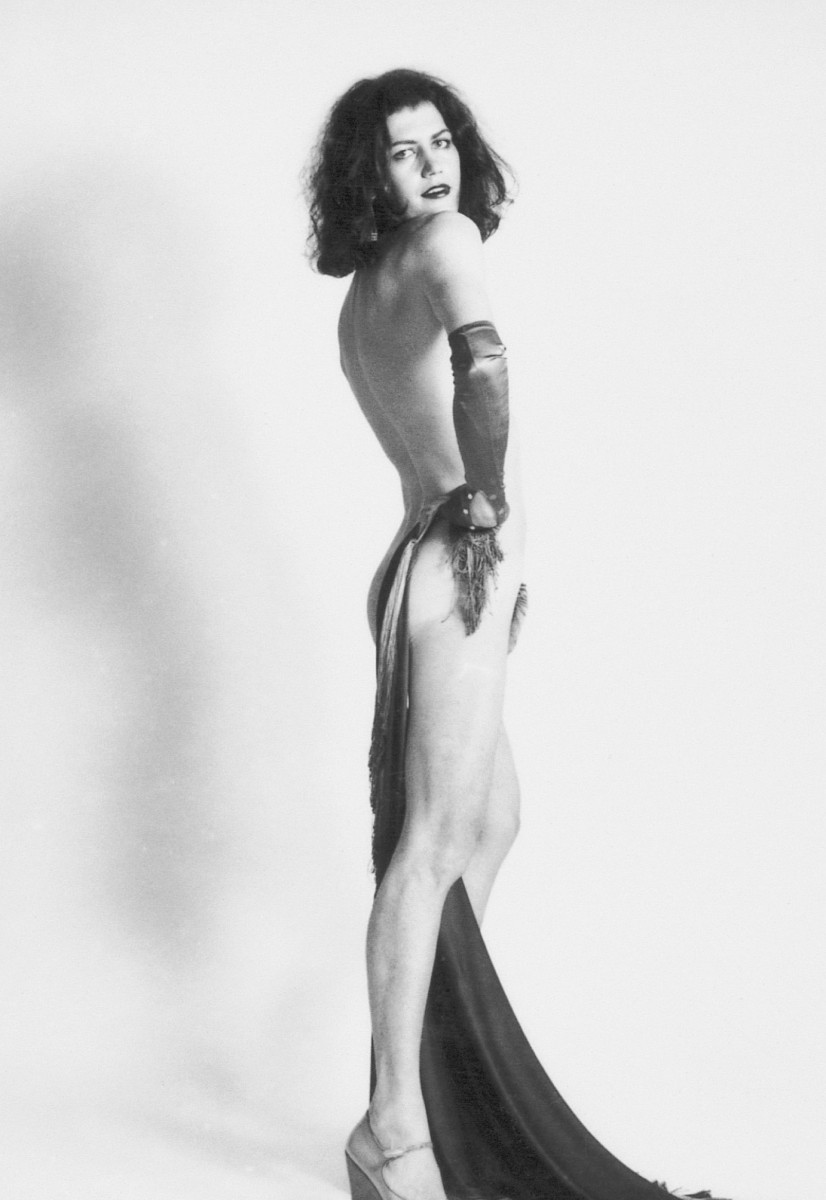

*** My performance persona, Alice Jitterbug wore female underwear. This was transgressive and illegal in some states. One could wear the clothing of the opposite sex, but men in particular had to wear male underwear to demonstrate that it was just a costume. I’ve tried to find the particular law/s in this respect to give specific reference here. At this distance in time I’m not sure if the legal situation was most vigorously pursued in Tasmania, even though we felt vulnerable to Queensland as well. Nonetheless drag queens and cross-dressers were subjected to whatever behaviour the police wished to dish out should anyone in drag have the misfortune to come into their custody.

**** Totschweigetaktik …’’death by silence’’ is… ‘‘an astonishingly effective tactic for killing off creative work or fresh ideas or even news stories. You don’t criticise or engage with what’s being said or produced or expressed; instead you deprive someone and their work or opinion of the oxygen of attention’’. http://gatesofvienna.net/2010/08/totschweigetaktik-death-by-silence/

***** Jacques Brel, Amsterdam, (1964) English lyrics as sung by David Bowie. Wikipedia state: Bowie’s studio version was released as the B-side to his single “Sorrow” in October 1973. … Brel originally stated that he didn’t want to “give his songs to fags”, and refused to meet Bowie, who nevertheless admired him.[6]

****** Andrew McGahan, Last Drinks, a reflection upon the endemic political corruption in Queensland in the 1980s, and the aftermath of the famous Fitzgerald Inquiry.

******* Facebook messages with Richard Bell, Feb 25 2016

For further reading on the GLBTQI history of Queensland I recommend Clive Moore’s ‘Sunshine and Rainbows’ published by University of Queensland Press (February 1, 2001) ISBN-10: 0702232084 ISBN-13: 978-0702232084